“Hello! We’re white, and we’re here to talk about racism!” If I were wearing a T-shirt with this slogan, my awkwardness would have been increased, but not by much. We knew when we started this journey that there would be difficult times. We knew that our plan of crisscrossing the country and visiting many of the National Park Service units would necessarily bring us face to face with some of the more embarrassing and shameful aspects of our country’s past. But I guess I didn’t expect to have so much self-consciousness come into play.

We spent the week in Tuskegee, Alabama, camped in the Tuskegee National Forest, with the objective of visiting two different NPS units: the Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site and the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site.

Tuskegee Institute

The Tuskegee Institute (the historic core of today’s Tuskegee University) is the only college campus that serves as a federal historic site administered by the National Park Service, and received the designation as a result of the school’s leading role in advancing education for African-Americans from its founding in 1881. Like many other HBCUs in the south, the school benefited from a second Morrell Act that helped fund schools committed to providing agricultural, mechanical and military training (“land-grant schools”), since under the second Morrell Act only non-segregated schools were eligible for funds. The school achieved many historic firsts, including being the site of the first VA hospital to treat African-Americans. Both its first principal / president, Booker T. Washington, and its lead science teacher, George Washington Carver, are significant figures in their own right who were born into slavery yet became leading academics, adding to the aura of greatness surrounding the school.

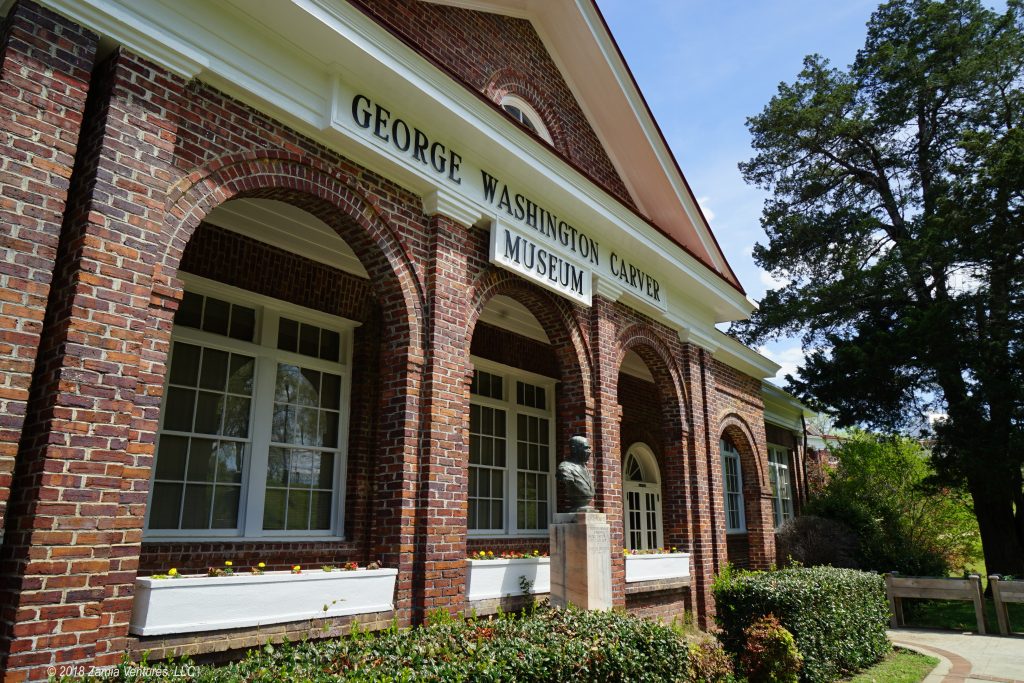

Since Tuskegee is still a fully functioning university, the areas that are open to the public as part of the NPS site are somewhat limited. There are basically two buildings: the George Washington Carver Museum and The Oaks, which was the private home of Booker T. Washington. Honestly, these sites were not all that great. Full disclosure: we did not tour the inside the The Oaks because we’ve been seeing plenty of furnished 19th century homes recently, and the tours were filled with very boisterous school kids. Yup, we are those curmudgeonly old people who get annoyed by loud kids in museums. But I did read all the interpretive materials at the site and online and I don’t think we missed that much by not seeing yet another 19th century home interior.

The Carver Museum was initially established by …. George Washington Carver, and it consists of the sort of information and materials you’d expect to see in a museum of oneself: clippings of his mentions in Life magazine, various awards he received, and personal items like paintings he made using locally-sourced pigments. The long lists of products he helped develop from peanuts, sweet potatoes and soybeans certainly demonstrate his ingenuity. The displays relating to his “road show” revealed his focus on providing practical help to poor farmers; he took agricultural science to the people with hands-on demonstrations carted around on wagons and then trucks. There’s no doubt that G.W. Carver was a highly respected figure, who seemed to have a genuine sense of wonder and gratitude for the bounty that nature produced. However, the museum was a little disjointed – why was there a large section describing the recent efforts of Tuskegee scientists to develop plants that can grow in space? – and didn’t do enough to tell the overall story of the Tuskegee Institute.

However, the grounds of the school were really interesting to see, since the exteriors of the buildings, many built with bricks made by students in the hardscrabble early days of the school, have been preserved to maintain the historic designation. The entire campus feels like a museum, with interpretive signage in front of all the historic buildings describing the original use. The closeness of the past is emphasized by the presence of a cemetery in a central location on campus, next to the chapel, where many of the school’s former faculty are buried.

The nearby memorial to Booker T. Washington includes a sculpture that powerfully communicates his mission to bring freedom through education. From the materials presented by the NPS, it’s apparent that Washington believed the American dream could be available to all, even impoverished former slaves. He frequently wrote and spoke about the ability of poor farmers to learn trades and improve agricultural practices in order to build financial security and therefore to have the breathing room to lead more engaged and elevated lives.

The name of the Veil of Ignorance memorial to Washington comes from its moving primary inscription: “He lifted the veil of ignorance from his people and pointed the way to progress through education and industry.” To see that level of optimism displayed by a man born into slavery, who came to Alabama during the harsh post-Reconstruction period and persevered for decades to build this institution, was humbling, to say the least.

Legacy Museum

Our favorite stop within the university, and the one that did the best job of telling the story of the Tuskegee Institute, was actually the Legacy Museum at the National Center for Bioethics in Research and Healthcare, located in the former hospital complex. Here we had a guided tour, which gave us the opportunity to have several awkward conversations centered around racism and the historic oppression of black people.

Tour guide: How do you think white people reacted to the establishment of the school here?

Us: Uh, not well?

Guide: Not true! A leading member of the board of directors was white!

Us (muttering): It was a trick question.

Of course, a few minutes later we learned that the first head of the very successful hospital left town because of oppressive discrimination and relocated to New Jersey, so I’m sticking with my original answer to that question.

The main focus of the Legacy Museum is on the medical achievements of the Tuskegee Institute, which included operating the leading hospital in the south that served African Americans. Tuskegee enticed the VA to open its first hospital to serve black veterans by donating land on the Tuskegee campus for that very purpose. Tuskegee was unfortunately also intimately involved with two of the worst ethical lapses in modern medical history, and the museum devotes plenty of attention to both.

In the notorious case of the Tuskegee syphilis study that concluded in 1972, participants in a federally-sponsored study on the long-term effects of syphilis were not advised when treatment (i.e., penicillin) became available in the 1940s because treating the patients would ruin the results. Of course, it’s no coincidence that the participants were all poor black men, who presumably were enticed to participate by the reputation of the Tuskegee hospital where the study was administered. It took until 1993 for the U.S. government to acknowledge the inhumane treatment of the study participants by formally apologizing and giving pathetically small reparations checks to survivors and their descendants.

Tuskegee also played a central role in cultivating and distributing the constantly-growing cancer cells harvested from Henrietta Lacks, a black woman who died of cervical cancer in Baltimore in 1951. The HeLa cell line is far and away the primary source of human cells for experimentation, and was used for decades without the knowledge or consent of the patient or her descendants. This has changed recently after reporting that informed the family about the situation, but it seems likely that the failure to bother obtaining consent for the use of the original tissue was related to the fact that it came from an African American woman who lived in the segregated south.

Thanks to the Legacy Museum’s focus on these difficult topics on its second floor, we had the opportunity to have even more conversations about race with our tour guide, this time while surrounded by photos of African American adults with syphilitic lesions and children with limbs twisted by polio. Needless to say, the Legacy Museum gave us a lot to ponder and discuss after our visit was over.

Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site

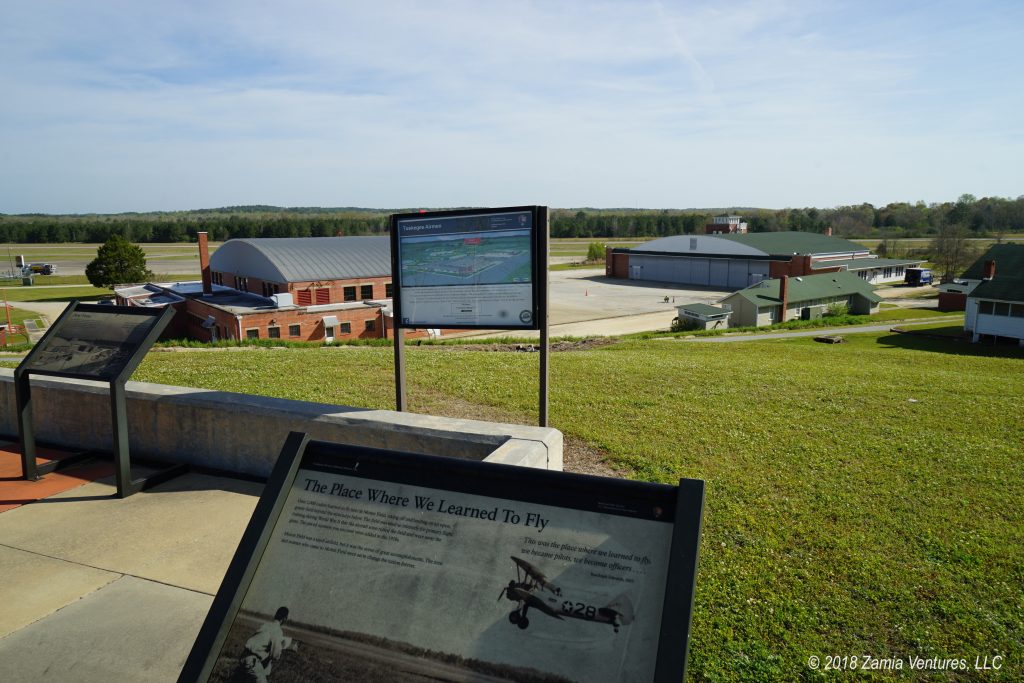

Located just outside town on the grounds of Moton Field, where the Tuskegee Airmen received their basic flight training, the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site was, in our view, a much better interpretive site. Although the airfield is still in use as a municipal airport for Tuskegee, the minuscule volume of general aviation means that virtually the entire airfield (and its strangely vast parking lot) is open to the public as part of the NPS unit. The two hangars devoted to interpretive displays are chock-full of great artifacts and information about the subject matter. The best part about this site is its laser-like focus on its time period (1941-1945) and its mission: telling the story of the Tuskegee Airmen, and explaining the significance of these African American pilots and ground crews in leading to the integration of the armed forces and advancing the civil rights movement.

But there was also plenty of awkwardness to be experienced, starting with our initial introduction to the site. We were greeted by a friendly African American park service employee, who encouraged us to watch an introductory film before heading into the main hangars, and we chatted with him while he cued up the video. It started out with a series of images and sounds showing and describing Jim Crow laws, segregated facilities, and lynchings in pretty strong detail, all to set the stage for the time period in which the 99th Fighter Squadron was formed as an experimental all-black military unit. Fun times! The virulent institutional racism of the time is obviously a critical part of the story, but I felt really badly that this guy has to listen to this video repeatedly, every day, while still being cheerful with visitors like us.

The interpretive site includes lots of artifacts large and small. It was cool seeing the planes used for training and the fighter planes used by the airmen, and various mechanical components maintained by the ground crews. The fact that the training aircraft were made of wood frames stretched with fabric was a good reminder that WWII occurred pretty early in the history of aviation. The site included plenty of tactile experiences like parachute silks and deconstructed airplane wings, and sample study materials containing photos of enemy ships and aircraft for identification purposes. We loved the detail of furnishing the office areas with period furniture, complete with old typewriters, metal fans, ubiquitous ashtrays, and 1940s calendars.

The best part of the site was how effectively it communicated the stark reality that these men literally flew side by side with other Americans and helped secure our victory in Europe, yet had to deal with segregated quarters on base and even worse treatment in America at large. It made me absolutely furious.

On a more hopeful note, the site also highlighted the patriotism of the members of the unit and their pride at being able to serve their country in full combat positions. A large collection of clippings from African American newspapers showed that the squadrons trained at Tuskegee were followed closely in black communities around the country and celebrated for their ground-breaking achievements. The men who deployed were well aware that they were leading the “Double V” movement, seeking victory for democracy both at home and abroad. Helping take down a racist regime in Germany was only the first step toward finally achieving the promise of American democracy in the form of securing civil rights for African Americans.

Quite frankly, I’m pretty amazed that people who suffered from segregation and disenfranchisement (to say nothing of lynchings) would still want to put their lives on the line for a country that denied their full humanity. But I am not surprised at all that Tuskegee Institute volunteered to be the site where these pioneering people – including plenty of African American women involved with maintaining the training aircraft – received their training. Our tour of the sites here gave us a new appreciation and perspective on African American history. Though we had several uncomfortable moments in the course of our visit, that discomfort comes from being pushed toward a fuller appreciation of the achievements and experiences of our fellow citizens, which is an important purpose of our journey.

Tuskegee National Forest

Meanwhile we’ve been camped in Tuskegee National Forest, where we’ve been enjoying free dispersed camping along with the slightly disconcerting sound of coyotes howling in the night (thankfully in the distance). We took several hikes on the Bartram Trail, keeping our mileage comfortably under 10 miles each time, and enjoyed seeing signs of spring in the blooming dogwood trees and wildflowers. Our portable solar panels have once again performed really well, helping us stay energized while camping off the grid. All in all, another successful week on the road.

Great report. These are subjects we rarely hear about and I know of few people who would choose to visit and investigate the history of this area. I learned a lot from this.

Thanks for such detailed stories.

Although some of these sites showcase the ugly side of our history, we’re learning so much about American history and developing a real appreciation for its complexities, so it’s worth it.

Ditto on Dagmar’s comments – very informative & detailed reporting. We thank you!

Linda & Bill

All the Andersons are loving hearing about your travels! Thanks for sharing!

Awesome, thanks for following!