On our way north from Tuskegee, we visited our first National Military Park: Horseshoe Bend. This small park includes the location of the decisive final battle in the Creek War in 1814, which resulted in the Creek people relinquishing to the newly independent United States their claims to over 23 million acres of land in the southeast (present-day western Georgia and virtually all of Alabama). The American military leader in the conflict was Andrew Jackson, and his victory in this battle and the subsequent Battle of New Orleans was the main source of his fame and ultimately contributed to his election as the seventh U.S. president.

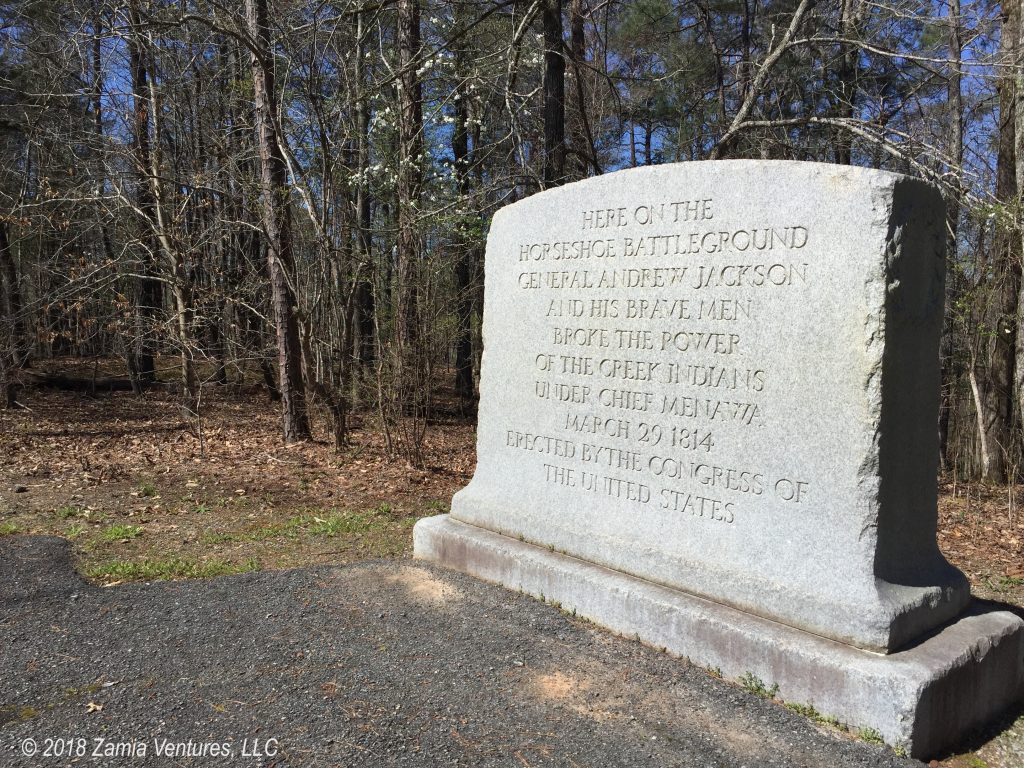

The park was established in 1959, so I think (but can’t verify) that it was originally intended to celebrate the success of Andrew Jackson, as suggested by the inscription on the large stone monument overlooking the battlefield. But the majority of the interpretation at the site is focused on an interesting fact: there were Native Americans, including Creeks, fighting on both sides of the battle. The NPS interpretation did an excellent job of setting the context for the battle, and the overall Creek War, within a civil war in the Creek Nation. The conflict was based on a fundamental disagreement among Creek people about the best way to respond to the encroachment of Europeans / Americans on their territory. Since the Creek people lived in what is now the southeastern U.S., they were interacting with European colonists from the very early years of North American colonization. On one side of the civil war, a faction called the Lower Creeks thought it best to attempt to emulate, cooperate with, and trade with the Europeans. This would mean becoming more agrarian, speaking English, and dressing in a more European fashion. The Upper Creeks, particularly the Red Stick faction, generally advocated a return to traditional ways, including more reliance on hunting and less reliance on trade goods.

The Creek people faced a genuine conundrum in deciding how to deal with the massive cultural disruption caused by the arrival and unremitting expansion of British colonists and then Americans. Both sides in the civil war had strong arguments supporting their approach, which made the conflict particularly difficult to resolve. Let’s compare the outcomes experienced by the different groups:

Red Stick Creeks who fought against US encroachment, including in this battle against Andrew Jackson: Mostly killed, but otherwise deported to Oklahoma

Creeks who adopted “white” ways, engaging in agriculture in established settlements: Mostly deported to Oklahoma during the Trail of Tears, but some killed

It’s not really clear that there was a right decision here. To make matters worse, this internal conflict came to a head at the same time that the US came into conflict with Great Britain in the War of 1812. The very uncertain long-term prospects of the new American nation must have made it even harder for the people caught up in the conflict to choose sides.

The battlefield itself is situated in a unique location, where the Red Stick Creeks took advantage of the natural topography to make their last stand. As seen in this map, a loop in the Tallapoosa River creates a small peninsula surrounded on three sides by water, and the Red Sticks built a barricade of wood and earth across the narrow neck. The community lived in a settlement erected at the end of the peninsula, away from the location of the battle. The barricade was so effective that hours of pounding by Jackson’s two cannons didn’t make a dent. The battle ended up being mostly hand-to-hand combat, and the larger numbers of the American forces prevailed on a bloody afternoon. The decisive event of the battle, however, was that some of the Native Americans fighting alongside Jackson swam the river and burned the village, effectively destroying the safe haven at the end of the peninsula, attacking from the rear, and forcing a battle to the death for the Red Sticks.

The park provides an opportunity to walk the terrain and imagine how the now-peaceful location became the site of a vicious fight. We took the three-mile walk around the park to see the relatively flat areas that served as the battleground and the village site, the wide river that offered less protection than expected, and the naturally rugged terrain surrounding the peninsula which made it hard to the Americans and their allies to approach this perfect defensive position. We were here just a few days after the anniversary of the March 27 battle, and our pleasant walk on a sunny spring morning provided an interesting contrast to the horror and desperation that the fighters on both sides must have experienced on the day of the battle. I particularly appreciated that the park service chooses to interpret the site with well-placed display boards, and not with weird life-size cutouts of combatants.

For us, imagining the world of 1814 put us in a good frame of mind for our plan to follow the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail later this year. It’s pretty amazing to think that, in 1814, Alabama was a “wild frontier” filled with warring Native Americans. It makes the Lewis & Clark journey of 1804-1806 all the way to the Pacific seem even more improbable. Thomas Jefferson’s thought that a small cluster of former colonies clinging to the Atlantic seaboard would need to know about the great western expanse of the continent seems laughably audacious.

American history is riddled with injustices and we have not learned much from our history.

It was interesting to hear about this battle and the expansion of white settlers from coastal areas to the western territories occupied by native Americans.

Keep these reports going…you are educating us all.

We were just discussing yesterday how it seems that so many monuments commemorate the “losers” even though they say history is written by the winners. Historic sites like this that tell about the last stand of a group of Native Americans are definitely giving us a more nuanced perspective on American history.