Since one of the guiding principles in our travels is to visit National Park Service units across the country, we wanted to see as many of our home state sites as possible before leaving Florida. As our path brought us to the west coast of Florida to visit family, we made time to swing by a secluded Gulf Coast point near Bradenton for a morning at the De Soto National Memorial. The memorial commemorates the supposed landing spot of the Spanish expedition led by Hernando De Soto that spent four years exploring what is now the southeastern U.S.

There’s no question that the expedition had a significant impact on the course of history in this part of the world. De Soto introduced a deep and abiding enmity between Europeans and native people, and the arrival of his troops (with their attendant diseases and pigs) virtually wiped out entire cultures in the southeast. The published accounts of the expedition also helped generate the first significant European interest in colonizing North America.

The memorial was established in 1948 at a time when the approach to history and historical interpretation was different from today, and there are quite a few aspects of the memorial that are, shall we say, problematic. Let me count some of the ways.

1. It’s not clear that this is actually the landing spot of the expedition. Through interpretation of very old accounts written in Spanish by people who were unfamiliar with the terrain, and some limited archaeological findings, scholars have deduced that the expedition landed somewhere on the southwest coast of Florida, likely near Tampa Bay but perhaps 70 miles south at Charlotte Harbor. The exact location is simply lost to the mists of time.

2. It’s definitely not clear that De Soto should be idolized. He honed his conquistador-ing skills as a captain with the Spanish armies that subjugated the native people of Central America and then the Incan empire. His goal was plunder to enhance his personal wealth, and his typical approach was to hold a village or tribal chief hostage until the community turned over all its resources to him, following which he might still kill the chief anyway. As one of the interpreters dryly noted, De Soto “was not there to make friends.” His approach to all the native people he encountered was one of total hostility and contempt.

3. There is some really heavy-handed Catholic framing of the whole expedition. One of the largest items located on site is a gigantic granite cross which, according to its inscription, commemorates the 12 Catholic monks and priests who participated in the expedition. The monument, sponsored by the Catholic Diocese of Venice, is apparently also dedicated to all priests who serve in Florida. The attempt to recast a naked grab for wealth, resources, and domination as a holy endeavor just strikes a weird note, especially since this huge cross was installed relatively recently, in 1995.

4. Based on the text of the legislation that created the memorial, a significant part of the justification for the project appears to have been that the federal government funded a memorial for the Coronado expedition in 1941, De Soto’s expedition was more important, and we in Florida wanted our own memorial. It seems this was historical one upsmanship at its best, not a real judgment about whether De Soto deserved a memorial. Note: Once we visit the Coronado memorial, which we will undoubtedly do if we are anywhere within a hundred miles of it, I’ll report back on its relative lameness.

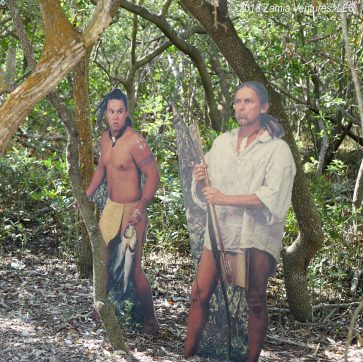

Anyhow, the National Park Service is obviously struggling to present information about this controversial historical event. To their credit, they are not simply lionizing Hernando De Soto, explorer extraordinaire. Rather, they are trying to present a more nuanced picture, highlighting that native people were already living in the area within complex cultures at the time the De Soto expedition arrived. Unfortunately, the main way they have chosen to do that is …. odd. The natural area of the park features a short but scenic trail through an ecosystem similar to what De Soto encountered. The NPS has tried to help visitors remember that the arriving Spaniards encountered Native Americans by placing life-sized cutout photos of Spaniards and Native Americans at intervals along the trail. Let me tell you, it is downright unsettling to be walking along a normal nature trail, observing mangroves, and suddenly see a life size photo of an Indian propped a few yards off the trail.

Less weird was the living history element of the park, which seemed to be aimed at children and offered lots of interesting hands-on experiences, like the opportunity to try on (very heavy!) reproduction Spanish armor. While I think the site could do more to highlight the complexities of the De Soto expedition, it seems clear from the unit’s foundation document that the National Park Service gets the issues. Here’s hoping the NPS budget will eventually allow for more than lame cutout photos to advance the interpretation of the site.

Another Great State Park

Meanwhile, we’ve been camped at Alafia River State Park southeast of Tampa, where a former phosphate mine has been turned into a wonderful wilderness area. The ponds and slag heaps left from the mine have long since been reclaimed as forest, creating unusual contours and elevation changes not normally seen in Florida. The mountain biking trails are famous, but we’ve stuck to the hiking and equestrian trails, which give the distinct impression that elves or nymphs might appear from behind the trees. (Anything but cutouts, please.) We’ve seen a lot of wildlife, and the most fun was watching ospreys nesting on property carry fish from the ponds to their nests.

7 thoughts on “Deconstructing De Soto National Memorial”