Confederate monuments have been much in the news, and the recent controversies have sparked some useful personal reflections. Growing up in the south, I didn’t particularly question the predominance of Confederate monuments. Mostly, I just mocked the maudlin, overwrought testimonies to the greatness and chivalry of the war dead which these monuments tend to feature. The most memorable one I have seen is the Confederate Monument in Jefferson County, Florida, placed in front of the courthouse in the small town of Monticello, Florida. The voluminous text is in serious need of editing, because of both its length and the excessive use of fevered language. But this monument is an outlier only because of the text — it is so completely ordinary to find elaborate monuments to the Lost Cause prominently displayed in communities large and small all over the south that no town center would be complete without one.

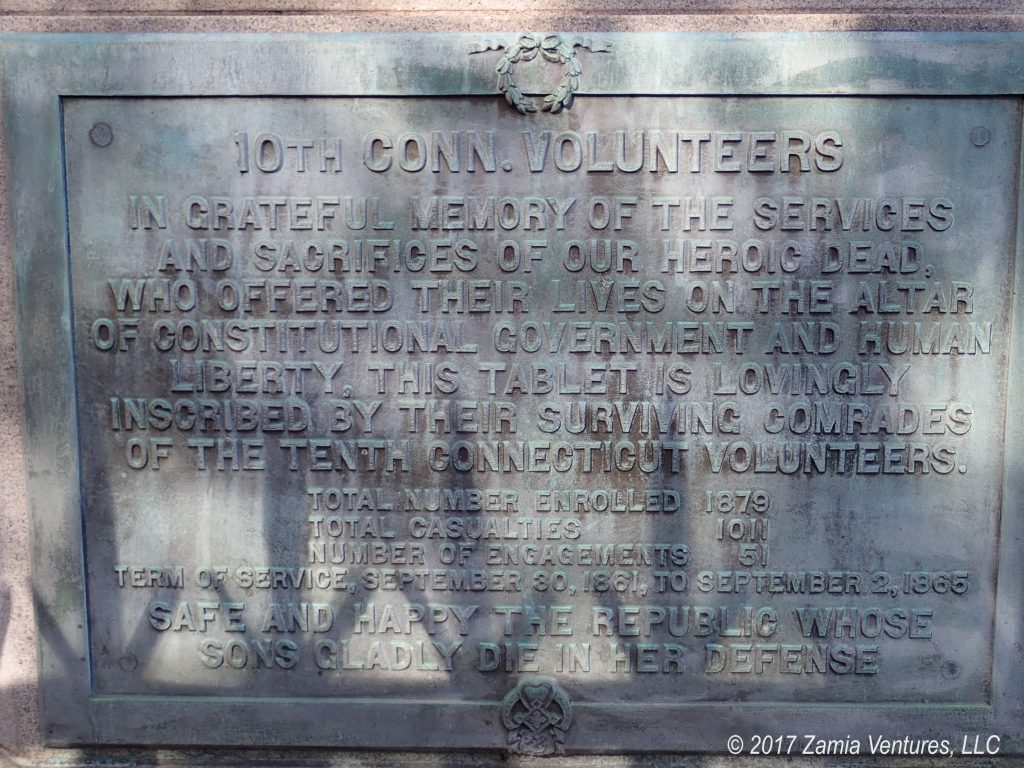

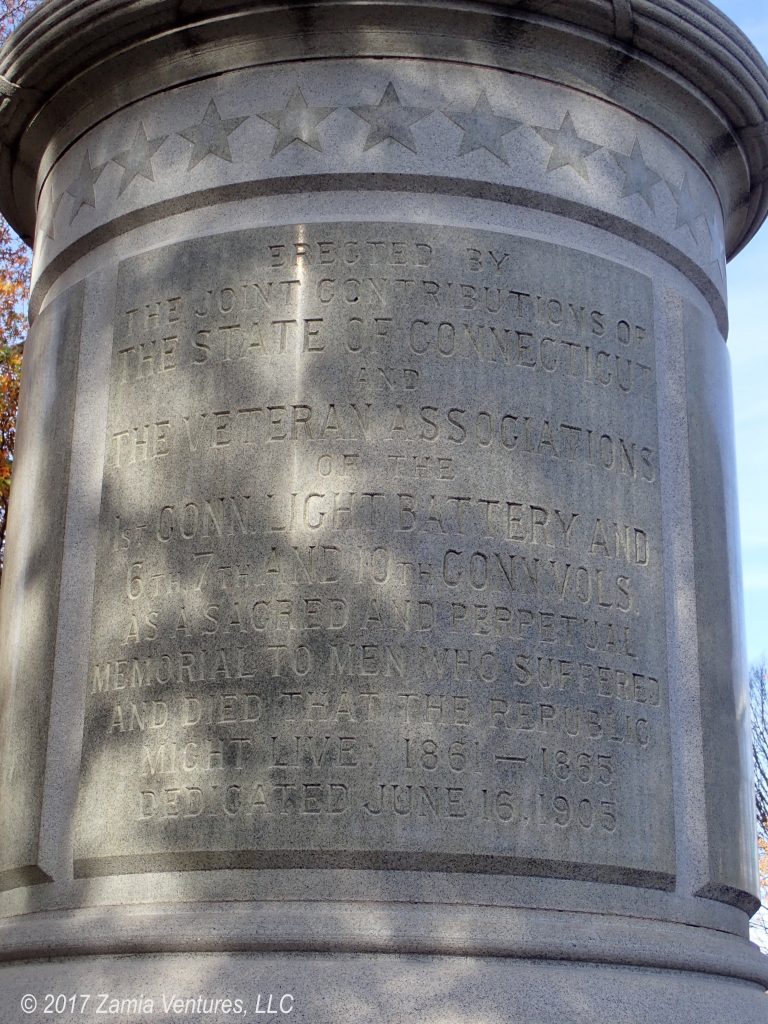

I distinctly remember seeing my first monument to Union war dead when I was in law school in Connecticut. I recall my total surprise in realizing that not all Civil War memorials were erected for the losing side. It was my own personal black swan event — never having seen a Civil War memorial that was not for the Confederate side, I had been lulled into the false assumption that none existed.

In retrospect, of course, it seems obvious that the victors in America’s bloodiest conflict would have plenty of monuments and memorials to their war dead. Rather, what’s truly weird is to have so many monuments to a political assembly that was (a) treasonous and (b) a short-lived failure.

The 20th century use of the Confederate cause as a proxy for white supremacy, beginning at the inception of the Jim Crow era and continuing into the present day, has caused me to change my thinking about these seemingly ubiquitous monuments.

The issue is personal because like a lot of people born in the south, my middle name is the last name of a prominent Confederate general — though my parents claim it’s not a direct namesake. The name is just part of the social currency of this region of the country, and gets used a lot even without a conscious effort to tie back to Confederate heritage.

Even more personally relevant is that I’m eligible for membership in the United Daughters of the Confederacy. My visit to the aforementioned Jefferson County memorial was prompted by family interest in genealogy, which unearthed the fact that a direct ancestor who lived in southern Georgia during the Civil War was a member of the Jefferson Rifles, a Confederate company raised just across the state line in Florida.

His service from August 1861 through April 1865 spans virtually the entire period of active conflict in the war. While my ancestor’s motives can’t be determined with any certainty, given what else we know about this fellow from family history research, I’m pretty sure he was in it for the money and the opportunity to travel the country on someone else’s dime.

Given the personal ties and my history of intellectual complacency on the issue, I’ve been trying to make up for lost time by thinking specifically about what should be done with these monuments throughout the south. To tackle the local angle, I tried to locate any Confederate monuments in Miami. It turns out that Miami has a pretty minimal amount of Confederate paraphernalia, and the story of Miami’s monument is potentially instructive for how to handle the controversy elsewhere.

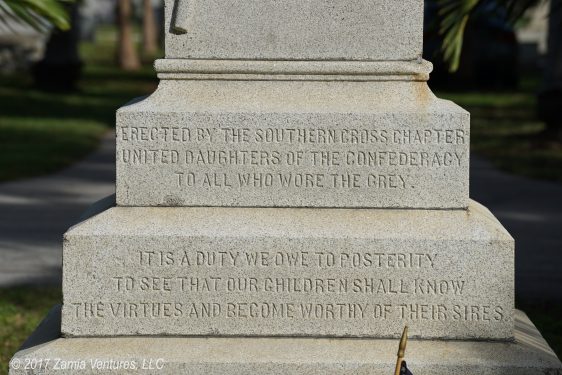

I was only able to find a single physical Confederate monument that was placed on public property in Miami. The memorial, sponsored by the UDC, was originally located in front of the Dade County courthouse. The timing of the construction (1913) and the placement in a prominent public location fit with the understanding that the monument was designed to reinforce the social commitment to white supremacy throughout the south.

Moreover, the text of the monument, a quote from Jefferson Davis, seems to communicate the desire of those early 20th century Miami residents to continue to support and advance the principles for which the Confederacy fought — i.e., human enslavement. It reads:

Erected by the South Cross Chapter, United Daughters of the Confederacy, to all who wore the grey. It is a duty we owe to posterity to see that our children shall know the virtues and become worthy of their sires.

So far, the story of the Miami Confederate monument lines up with the standard narrative throughout the south. But then Miami’s story gets sort of weird, most likely because of its limited cultural affiliation with the Confederate cause.

The general absence of memorials in South Florida makes sense to me because Miami basically didn’t exist at the time of the Civil War. Florida became a state in 1845, a mere 16 years before active combat began, and at the time the vast majority of the population lived in Tampa, St. Augustine, and the areas close to the Georgia border. Of course, the relatively few residents who inhabited the state were deeply enmeshed in a slave economy. According to Wikipedia, “by 1860, Florida had 140,424 people, of whom 44% were enslaved and fewer than 1,000 free people of color.” Florida was a member state of the Confederacy, and sent a contingent of (white) soldiers to fight in the war.

However, down here in South Florida most of the inhabitants in 1861 were Seminoles, who clearly had no particular interest in joining the army of the Confederate States of America. The first boom times in the Magic City began at the end of the 19th century, and attracted entrepreneurial people from many places, including the north. Civil War veterans among Miami’s early residents were probably equally likely to have served for the Union or the Confederacy.

So the context for the Miami Confederate monument was a community with something much less than deep ties to the Confederate cause. Also, Miami is at its heart a city that values expediency over principle. That may be why public corruption is so rampant, but also explains how the Confederate monument was quickly relegated to an unobtrusive part of the city.

By 1927, the original county courthouse needed to be expanded thanks to the explosive growth of the city. In the process, the Confederate monument, then only 14 years old, was disassembled and packed off to the City Cemetery of Miami. The obelisk that originally topped the monument had been damaged, so that was discarded completely. The remaining sections were reassembled in the current location, and the surrounding plot was dedicated as a final resting place for Confederate veterans who might die in Miami without any close family members to share other plots in the cemetery. The hasty process apparently changed the configuration of monument — the Stars and Bars originally appeared over “1861-1865 Our Heroes” instead of on the back — and no one cared enough to correct this.

The upshot is that what may have originally been a serious effort to reaffirm Confederate, white supremacist values pretty quickly ended up as a slightly banged-up memorial to war dead, which seems entirely appropriate. Despite the horrible principles and practices endorsed by the slave-holding southern states, Confederate veterans were not all monsters, and their descendants deserve to memorialize their deceased ancestors in a positive way. We visited the City Cemetery on Veteran’s Day, and were pleased to see little U.S. flags adorning the plots of the many veterans in this historic cemetery.

After some thought I was even comfortable with having U.S. flags placed on the graves of the Confederate veterans, which you see in the pictures. They were clearly Americans who served in a military capacity, even if in service of a rebellion, and the states they served were ultimately restored as part of the our country. The only way to truly reconcile the Confederate states back to the U.S. was not to demonize the individuals who participated in the war, but to attempt to work cooperatively to forge a better nation together.

Abraham Lincoln understood this clearly and urgently, as shown in the famous finale of his second inaugural address:

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

I find it interesting that an early good solution to the Confederate monument problem arose organically in a multicultural city like Miami, where everyday living necessarily involves interacting with people of many different backgrounds and ethnicity. Sending the monuments away from the public square and to the cemetery, where they can join all the other memorials to honored dead, is the obvious solution to the challenge posed by these loaded memorials. Miami’s history of progressive thinking is checkered, to say the least, but the city definitely got things right with the treatment of its Confederate monument. It’s a model for other cities to consider as they examine what, exactly, they are trying to communicate by maintaining these items on public property.

I have been volunteering at the Miami City Cemetery for several decades and I always put American Flags at the Graves of the Killed in Action just under 50 in total . I was the one to put American Flags at the Confederate Monument. Agree Miami is different to say the least but we can’t erase History, Ronnie Hurwitz .Great post by the way .

Ronnie, thanks for the nice comments and thanks for all that you do with your volunteer work. I am so appreciative of community volunteers who help keep our history alive and relevant.