Since we are not traveling this summer, we decided to volunteer with sea turtle patrol during nesting season, which runs from May 1 through October 31. Five species of sea turtles nest on Florida beaches, all of which are endangered or threatened. The most common are loggerheads, greens, and leatherbacks, while Kemp’s Ridley and hawsbill turtles are only occasional nesters. In particular, Florida hosts the nests of approximately 90% of the North Atlantic population of loggerheads, so the success of our nests is vital for the future of the species.

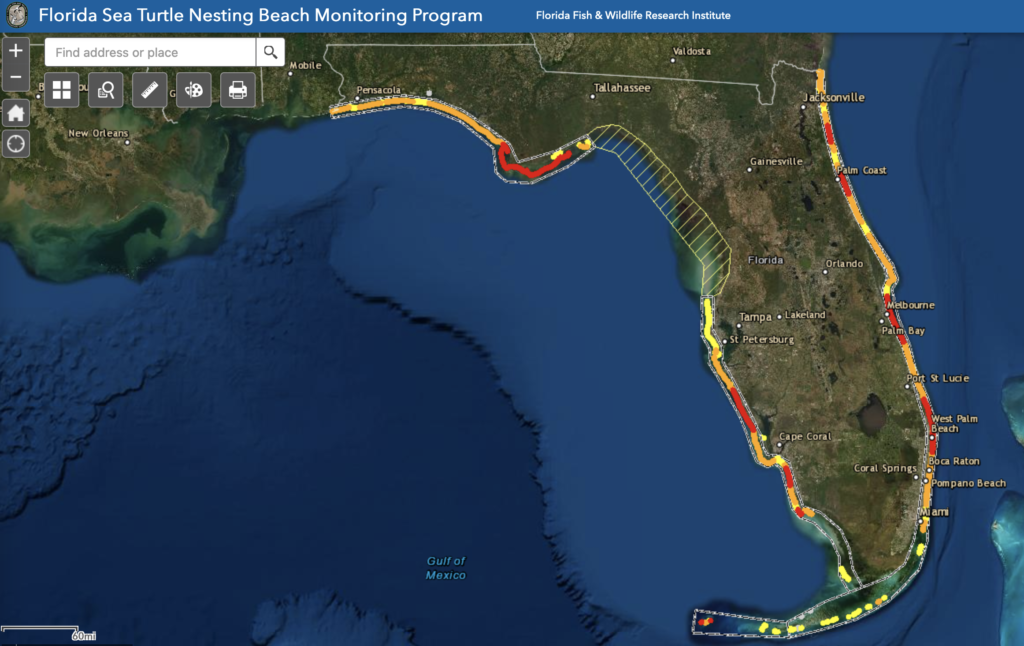

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) spearheads the very extensive monitoring of sea turtle nesting around the state, which occurs in seven regions with genetically distinct populations. FWC offers loads of information on these interesting animals on their website. In the map below, the relative density of nesting within each region is shown, with red being the highest density. All these beaches are monitored with a high degree of granularity, with nesting data going back several decades.

While the Northwest (panhandle) region is not the largest sea turtle nesting region in absolute numbers, our part of the panhandle has the greatest nesting density within our region. FWC reports that in 2018, 2019, and 2020 our county reported, respectively, 506, 807, and 549 nests, and most of those are found on the nice sandy beaches of St. George Island, Little St. George (owned by the state), St. Vincent (a national wildlife refuge), and Dog Island. Given that a typical turtle mom lays 4 clutches per season — then takes off 1-2 years before nesting again — these numbers are consistent with research estimates of 323–634 nesting females within our loggerhead subpopulation. For comparison, Palm Beach County recorded nearly 30,000 nests in each of the last several years, making it one of the highest density areas within the very busy Southeast region.

Don’t Try This at Home, Kids

Since sea turtles are endangered species, all activity involving the turtles requires a permit from FWC. Each permit covers a specific geographic area, a specific set of activities, and specific group of authorized individuals. Everything I describe about our activities below is Permitted Research under MTP-143. The permit covering our volunteer turtle patrol is held by a person who works at ANERR (Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve) and coordinates our volunteer activities. Each team that surveys a different beach around the state operates under a separate permit that has different practices. For example, we collect data on every single nest in our area, while turtle patrollers in the Southeast section take a sampling approach, collecting data on every 10th nest.

Patrolling for Nests

The first and most obvious activity of turtle patrol is — you guessed it — patrolling. We are expected to be on the beach with our volunteer partner at first light every single day to walk an assigned 1-mile section and identify any crawls and nests. “First light” is officially defined as a half hour before sunrise, which means we are getting up waaaaaay earlier than I like.

Every. Single. Day.

But one benefit is that in just a few months we have collected approximately 97 billion photos like these:

Also, we begin each morning with a two-mile walk on the beach, which is not a terrible way to start the day.

Destroying the Handiwork of Children

Another part of our role is helping our visitors comply with our local “Leave No Trace” ordinance. This means moving beach chairs and tents off the beach if they were left overnight, and picking up assorted pieces of fun gear, usually partially buried, that were left behind on the beach. We have already collected enough goggles, snorkel masks, toy shovels, fishing lures, and lost sunglasses to stock a beach outfitter store.

Our turtle protection ordinance also requires people to undo any earth-moving work on the beach, so many mornings we are filling in deep holes in the sand and knocking down elaborate sand castles. The large holes can trap both turtle moms and hatchlings, but sand castle moats really only become an issue during hatchling season because newly-hatched sea turtles are quite tiny. If they get stuck in a moat on their way to the ocean, they are easy pickings for crabs and gulls.

Identifying Crawls

While appreciating sunrise colors and stomping on sand castles is plenty of fun, the whole point of this exercise is to find turtle tracks. Turtles are generally nesting on the beach during the dark of night so by being on the beach first thing in the morning we can find their tracks. The very distinctive tracks are easy to spot as we stroll the beach.

As part of our training we learned to use the shapes and sizes of the tracks to distinguish the different species of sea turtles that nest in our area, but the vast majority of our nesting activity is loggerheads. Not every emergence from the ocean results in a nest; sometimes the moms decide the location is not suitable and return to the sea without laying eggs. For each of these “false crawls” we collect the GPS location and the width of the track, along with other pertinent data like whether the turtle made it above the high tide line and whether human-made structures like sand fences appeared to interfere with the turtle’s activities.

Finding Nests

When we see those unique tracks we sure hope to find a nest at the highest point of the crawl. We follow the landward crawl up the beach, tracking the turtle’s movements into the dunes in many cases, in order to locate any spots where she might have dug her nest. There may be a few digging attempts before the turtle decides she has found an appropriate spot. Nest hunting can involve detective work like looking for dune vegetation that’s no longer firmly rooted and looks to have been dug up.

Once we locate the possible nest site, we dig a small exploratory hole in an effort to confirm that we have eggs. The turtle eggs look like ping pong balls and the top eggs in the clutch are usually not much deeper than my forearm. As the person on our team who digs for eggs most frequently, I have found that the texture of the sand is the biggest clue in finding the egg chamber. Very hard, compacted sand was not recently excavated and means we are searching in the wrong spot.

Once we verify the location of the egg clutch, we replace the sand and center a metal screen over the top to discourage predation by coyotes. Conveniently, this also helps cut down on digging by curious visitors. Every nest is logged by GPS, marked with poles and survey tape, and further marked with a survey flag in the dune line. That dune flag will help us identify any total washouts that include the loss of the poles and screen, which could happen in the case of significant storm surge.

Monitoring Our Nests

As part of our patrol, we do a daily check on each of our marked nests to see if there is any evidence of predation, overwash by high tides, or other activity around the nest. Sea turtle eggs incubate for approximately two months, so we don’t expect to see any hatchlings until August. Later in the season I’ll fill you in on our activities related to the hatching process. Spoiler alert: there is even more data collection involved.

Very Special Turtles

The overwhelming majority of the nests on St. George are loggerhead nests, but we occasionally host nests of the rarer leatherback and green species. We were lucky enough to find a green nest in our section one rainy morning, and these rare turtles receive extra special treatment. A marine biologist who works at ANERR has a research permit for the rare species that includes SGI, and she was able to make our nest part of her research. She located the egg clutch — quite a feat with the extra-large green turtle nests — and carefully removed about 25 eggs, making sure not to alter their original orientation. She placed a data logger inside the clutch before carefully replacing each of the eggs and covering up the nest. The sensor will record temperature, humidity, and movement, among other things, to help expand our knowledge about the incubation process for green sea turtles. This is the first time a green nest will be studied so closely in the Florida panhandle, and we are thrilled to be part of the process.

What a great post. Thank you for sharing your patrol work adventures and how it all fits into the bigger picture of turtle conservation efforts. Such a worthwhile effort!

Even though I’ve lived in coastal areas of Florida my entire life and have spent plenty of time around sea turtle rehab facilities, I’ve never been this involved with the science or the conservation efforts. I’m really enjoying learning more about turtles and doing the hands-on work.

This is such a cool, interesting, and beneficial way to spend your summer! Getting up every single morning before daybreak for MONTHS has got to be tough, but I’m really glad you finally started getting turtle nests—and even a green turtle nest! You are probably never going to spend an entire summer in Florida again, so this was the perfect time to do it. (Maybe I’m making an assumption here, but I know Eric and I are never again spending an entire summer here.)

I’m wondering why they don’t enlist more volunteers so that you could split the patrol duties with other folks and not have to be out there every morning? Anyway, thank you guys for doing this and making such an important contribution to the turtle conservation efforts. We definitely want to tag along one morning…can I come in my pajamas?

The biggest drag about this volunteer gig is the daily grind of getting up every single day. Now, we do have a volunteer partner and we have covered each other at times when we each have other commitments. Ken and I have definitely discussed the fact that, if we did this again, we would try to set a regular schedule with another volunteer to walk three days together, two days covered by us, and two days covered by the other volunteer. That way everyone gets a bit of a break. I have a renewed love for the workers’ advocates who brought us the five day work week, for sure.

You are welcome to join any time! It’s actually a lot of fun once the getting out of bed in the middle of the night part is behind you.

While I have enjoyed all 97 billion of your beautiful sunrise photos, it’s nice to get a deeper understanding of what it is you all are doing out there. It’s obviously important work and heartening to know there are so many people willing to crawl out of bed before sunrise, for months on end, to make sure these turtles survive. I do like that part of the payment for your efforts is that you get to kick over kids’ sand castles. “Damn kids… get off our beach!” It’s also nice (in an annoying way) that you all make sure no plastic crap gets left on the beach and washed into the ocean.

Seriously, why are humans so annoying?

Anyway, I’m glad to see you guys are finding nests now and I’m sure it’ll be gratifying when those little ones safely hatch and head for the water in a couple weeks – all thanks to you.

I am pretty amazed by the dedication of the entire volunteer corps. Florida has over 1,000 miles of coastline and most of those miles are patrolled daily for half the year by people willing to put up with heat, rain, bugs, and other challenges to help sea turtles survive. It’s truly impressive. I can’t wait to see the results of the season in the form of hatchlings, though I also have to remind myself that their survival rate is pretty low and I can’t get too attached. The circle of life is cruel!

While I, too, have “suffered through” all 97 billion of your sunrise photos, we were almost as excited as you when you were finally able to post your first nest find! If I were to spend a summer in Florida, turtle patrol would be high on my to-do list — and I have zero problem being up that early. Cannot wait for the baby turtle pics!!

It’s a little concerning that the nesting started so late, and numbers are way down statewide, but we’ll have to wait until the end of the season to find out if the numbers recover. I am pretty confident that several of our nests are high enough in the dunes that they will make it through incubation even if we have storms this summer, so I too am eagerly awaiting baby turtles!

Thank you two for your devoted contributions to patrolling, studying & saving Florida’s turtles.

We LOVE turtles!! We look forward to your future posts especially with the little hatchlings.

Thank you too for the gorgeous photos. You’re eyes are seeing glory.

We’re really enjoying the direct involvement with the turtle patrol, even though our total nesting numbers in this area are tiny compared to our old stomping grounds in southeast Florida. Now that we know how much work is involved in finding and monitoring all the nests, we’re actually pretty glad we don’t have thousands here!

This edutainment excursion is good for young children as well as grown-up. Going for a turtle patrolling can help in creating awareness among people about preserving turtles.