Our turtle patrol duties are at an end, and the results are not great.

But before I share the depressing news, let’s review what we were up to during turtle season, which runs from May 1 though October 31. In my earlier post about turtle patrol, I mentioned that our main activity in the early part of the nesting season is to identify nests, including logging data about the species and GPS location. Under the terms of the FWC permit for our beach — remember, this is all Permitted Marine Research Under MTP-143 — we place a metal screen over the egg clutches and rope off the nest area with surveyor’s tape. We continued patrolling every day, rain or shine. We ended up with 18 marked nests, and our last nest was laid August 5. Many nice sunrises were also viewed.

In addition to looking for new crawls, our daily patrol duties involved checking on each of the existing nests. We were primarily on the lookout for signs of predation; our most common predators are coyotes and ghost crabs. Luckily we only saw a few eggs that were pulled from a nest and consumed by a crab. A hungry coyote will devour the entire clutch. We also had several nests that were laid quite close to the water, and the natural course of erosion brought them perilously close to destruction. We said encouraging words to these nests, which I am sure helped them hang on against the odds.

The time frame for turtle incubation is 50-70 days. At 50 days, we started looking closely for signs of hatching. If a nest reaches day 70 without hatching, it is assumed to be a failed nest. That could be a result of predation, damage to the eggs from the roots of dune plants, egg infertility, or any number of other reasons. We perform nest evaluations on each nest, which takes place either three days after hatching or at day 70. The evaluation involves excavating the egg chamber and counting up the contents: hatched eggs, undamaged but unhatched eggs, damaged eggs, pipped (partially hatched) eggs, dead hatchlings, and live hatchlings. The numbers provide a picture of the total size of the clutch and the success rate. We also record the depth of the top and bottom of the egg chamber. The contortions necessary to dig into these egg chambers really highlight the non-stop glamour that is turtle patrol.

Our hands-on training on how to evaluate a nest gave us our first chance to interact with turtles. We observed a 70-day evaluation that was expected to mainly consist of counting unhatched eggs. But when our lead volunteer / trainer dug into the egg chamber, it was full of baby turtles! She pulled a few out to make sure they were alive and fully developed (the egg yolk sac was fully absorbed). We had fun examining these teeny little guys. Then the rest were covered up and left to emerge on their own. The few hatchlings that were pulled out spent the day in a cool, dark, quiet place — namely, in a bucket of sand in the volunteer’s closet, covered by a light towel. That evening we met on the beach to release them. Under the terms of our permit, we only release the babies before sunrise or after sundown. Releasing the hatchlings at dawn or dusk mimics their normal emergence behavior and gives them the cover of (relative) darkness to avoid birds on the beach, fishing pelicans, and predatory fish as they make their way out to the floating mats of sargassum seaweed where they will spend their youth. As soon as they hit the sand, the little ones motored down the beach and headed off to sea, giving these turtle patrollers a much-needed sense of accomplishment.

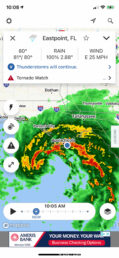

We had our first taste of tropical weather when Tropical Storm Elsa made landfall east of us on July 7. We mostly experienced rain, but the storm surge overwashed a few of our nests, which put them at risk. Turtles breathe air, and turtle eggs need to have continuous gas exchange to develop. Being underwater for any significant amount of time essentially drowns the eggs.

We marked our first nest on June 6, and it reached 70 days without any signs of hatching on August 15. That one was always a question mark — we had been unable to locate the egg clutch, despite all appearances of being a nest, so we marked it with tape as a cautionary measure. Since nothing ever hatched, it turned out to have been a false crawl (not a nest). We removed the tape, pulled up the poles, and hoped for more success on our next nests.

The next day, we had TS Fred.

Although the storm was only a tropical storm and never reached hurricane strength, it still packed a punch. We happened to be directly in the forward right quadrant, the strongest part of the storm, and experienced sustained winds over 50 mph with gusts up to 65. The relentless wind pushed water up the beach, with the storm surge completely consuming our wide beach and bringing pounding surf all the way up to the dune vegetation. When we walked our beach stretch the following morning, we found that the water and wave action had totally reshaped the contours of the beach. The raised escarpments where we had our precarious nests were completely gone, replaced by a perfectly flat, smooth beach. Twelve of our marked nests were gone without a trace — poles, screens, and all. We recovered a couple of washed up screens, but the main clue about the former location of nests was the dune flags we placed in the dunes above each screened nest. That morning, most of our dune flags looked out on a nest-free beach. The five nests that still had their poles and screens in place were mostly located in the dunes so were spared the brunt of the wave action. But when we examined them we saw that all had experienced some degree of overwash during the storm. Only time would tell if it was minor enough for the nests to survive.

We tried to remain hopeful about our remaining nests, only to have the 70 day windows close one by one with no signs of hatching. When it came time to do the evaluations, the best advice we got from a more experienced volunteer was to invest in some latex gloves. Trust me when I tell you that decomposing turtles do not smell good, do not feel good, and are definitely not something you want to pick up with your bare hands.

But then! One morning we finally saw what we most yearned for – signs that baby turtles had actually emerged from one of our nests. There were four tiny little versions of the distinctive turtle tracks coming up out of the nest. Following the tracks, it was clear that three of them headed right down to the water. The fourth set of tracks ended abruptly when the baby turtle encountered a ghost crab.

While the turtles usually emerge from the nest all at once in a “boil,” in some cases a few will emerge one night followed by the rest of the clutch the following night. That’s the reason we wait for three days after the first sign of hatching to evaluate the nest. Unfortunately, we never saw any further signs of baby turtles hatching from this nest.

On the final day of our turtle season, we performed a 70-day evaluation on yet another nest that never hatched. This nest was fairly low on the beach and we knew it had been under a substantial amount of water. So you can imagine our surprise when, after pulling out dozens of unhatched eggs, we found four live babies in the nest! I think the few surviving turtles were too small to push all the unhatched eggs out of the way and get to the surface of the sand. Since it was at the cusp of sunrise, we pointed these four to the ocean and made sure they reached the sea.

So for those keeping score at home, these are our numbers for the season:

- 18 nests marked

- 1 was not a nest at all

- 12 were completely wiped out in TS Fred

- 5 were overwashed with significant water and 3 of those had a 0% success rate

- 1 nest resulted in 4 live hatchlings, and one of those got nabbed by a crab on the way to the water

- 1 nest never hatched, but at evaluation we found 4 live turtles in the nest and released them

In addition to all the turtle data we gather, we also track our volunteer hours. So I can say with confidence that Ken and I collectively invested 340 hours of volunteer time, monitored nests that contained well over 1,000 eggs, and yielded a whopping seven turtles. Seven! I guess now we understand why no one ever says that wildlife conservation work is easy.

But let’s end this post on a happy note. The survival of sea turtles does not depend entirely on what happens on our assigned 1-mile stretch of beach. There are plenty of other nesting beaches along Florida’s 1,000+ mile coastline. Here on the island, we had plenty of nests that hatched with great success rates before Fred arrived on the scene — just none in our section. And there were some nests that managed to survive Fred and hatch a full brood later in the season — just none in our section. But thanks to volunteering with turtle patrol, we saved four lives. Those little ones we found in our final nest would never have emerged on their own. But because of our work, we gave four tiny turtles a chance at life by getting them to the sea. That’s a fine return on investment in my book.

Oh, man… this is tough. You guys put so much effort in and to have it end so sadly just stinks. Mother Nature can be brutal, no question. But, like you said, absent your efforts, some of these little guys never would have made it, and if it weren’t for folks like you doing this work all over Florida, these creatures wouldn’t stand a chance. What you guys have been doing these past several months – all the work, the training, the early mornings, for these helpless critters is beyond admirable. I’m glad you got to play with them if only for a bit, and I LOVE the video at the end – though I do wonder how much of a header he took going off that ledge. 🙂

The turtle at the end was fine! He/she toddled off to the sea. It’s the one in the photo at the top. That sand ledge was only about 6 inches high, though it looks massive compared to the tiny turtle.

While we are disappointed at the overall numbers, it was redeemed at the end by actually pulling some live turtles out of a nest! And we know it’s just bad luck to get hit with a tropical storm when most nests are still incubating. Without that one storm — or with a storm coming later in the season after most nests hatched — we would have had a very different experience. And, hey, someone’s got to collect those sunrise pics.

This brought me to tears…not because of all the turtles that were lost (although that does make me sad), but because you saved four little turtles!! Without you, they wouldn’t have had a chance. Your video absolutely made my day.

I also loved your photos of your obvious delight in finding the hatchlings. And those photos of you two facedown checking nests, LOL. What an experience! Thanks for your many months of dedicated effort and for documenting the journey for us. We enjoyed all of your sunrises, too. 🙂

Despite the lackluster numbers, we really enjoyed our experience. It was the ultimate in hands-on citizen science! And it gave us an immense appreciation for how much is done by volunteers, since the vast majority of Florida’s sea turtle nesting beaches are monitored by volunteers like us. That’s a huge amount of volunteer hours spent annually to identify and document and measure all those nests. Also, all those volunteers can’t be shy about passers-by staring at their rear ends, because the face down posture and the stoop being demonstrated by Donna are what most curious onlookers are treated to.

I had thought for some reason that the storms brought your turtle patrol season to an end, but I am happy to see they did not. I can only imagine what a heartbreak it was to have to go out and view the storms’ ravages on those nests you worked so hard to protect. But seven little adorable shelled critters have a chance that they may not have had without your diligence and care. Well done, Citizen Scientists!!

Thank you! Despite the storm damage, we still had to go out every day to look at our 5 nests that survived the storms. We also checked the general area where we had dune flags in case the storm washed away the poles and screen but somehow left the nests in place (this did not happen, at least not in our area). It was pretty grim for a while but the pleasant discover of live babies on our very last nest cast the whole experience in a happier light.