Our second full week in Tucson offered a chance to dive deeper into the offerings of this vibrant little city. By staying in one place, we grew more accustomed to the rhythms of the city, including but not limited to the training schedule of the Air Force base located near our campground. We focused our energy on some new destinations, and also revisited some places that were intriguing enough to warrant a second look. The highlights:

Tumacacori National Historical Park

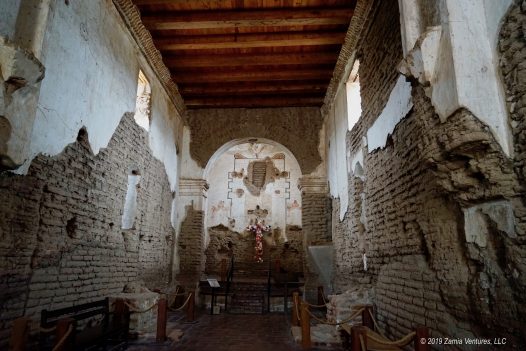

After visiting the nearby Mission San Xavier del Bac, which has been heavily restored and continues to operate as a Catholic church, we were interested in digging further into the history of the mission system. For a more academic approach, we headed to Tumacacori National Historic Park. This NPS site is located about 40 miles south of Tucson, and preserves the ruins of three separate Spanish missions with a focus on the Tumacacori site.

While the NPS sites are mere ruins, we found the ranger-led tour and the museum to be packed with interesting information. Instead of just eulogizing the valiant priests who headed up these missions, the NPS site presented the missions for what they were — long-standing native villages that the European priests essentially parachuted into. To fit in and communicate their message, priests learned the local language. Several of the missions in the system (the visitas) didn’t even have permanent clerical staff, but instead were visited on a periodic basis by a traveling priest. In short, the missions were part of existing native cultures, and daily activities in missions was dominated by the native people who populated the communities and who did all the work of growing food and building structures.

The NPS took time to examine how the appearance of the Europeans changed the power dynamic of the region, and what motivated the native people to cooperate with the priests. The people of the established O’odham villages far outnumbered the handful of priests who operated the missions and could have easily ejected the Europeans from their midst, yet chose to cooperate. Some of the benefits to the O’odham included the introduction of new species for cultivation, chiefly wheat, and the introduction of European livestock like pigs, cattle, goats, and horses. The alliance between the O’odham and the Europeans also strengthened the native peoples’ hand against their traditional enemies, the Apache. On the other hand, some of the negatives from living in mission communities included being infected with European diseases that wiped out vast swaths of the population, and having most of their traditional territory handed out to European settlers.

The high rates of death at mission communities led to the development of a new architectural feature: the mortuary chapel. Although the germ theory of disease was not well understood, it was quickly determined that placing the body of a recently deceased person in the main church where the entire community congregated was a terrible idea. As a result, in New Spain all churches were required to have a separate chapel for placement of the (many) dead bodies awaiting burial.

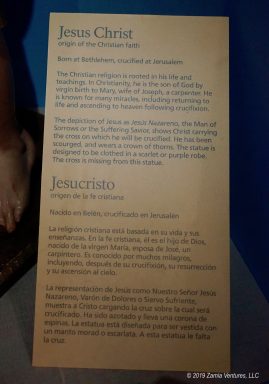

Unlike San Xavier del Bac, which was continuously occupied, the mission community at Tumacacori withered over time and was abandoned by the middle of the 19th century. The few remaining families packed up the “santos” — the wooden images of holy figures that occupied the niches in the church — and headed north to San Xavier del Bac. Without regular maintenance, and with the neighbors absconding with reusable building materials, the adobe structures began a long, slow decline. The remaining buildings record a century of graffiti as part of the cultural heritage of the site, which adds to the richness of the history. Overall, we thought Tumacacori took a much more nuanced approach to presenting the history of the missions, and we enjoyed exploring the rambling ruins at the site. I was also looking for a less religiously-tinged description of the missions, and got all that I might have wanted in that regard in the captions that accompanied the santos. It would be hard to be more detached than the clinical description of Jesus as “Origin of the Christian Faith, Born in Bethlehem, Crucified in Jerusalem.”

Titan Missile Museum

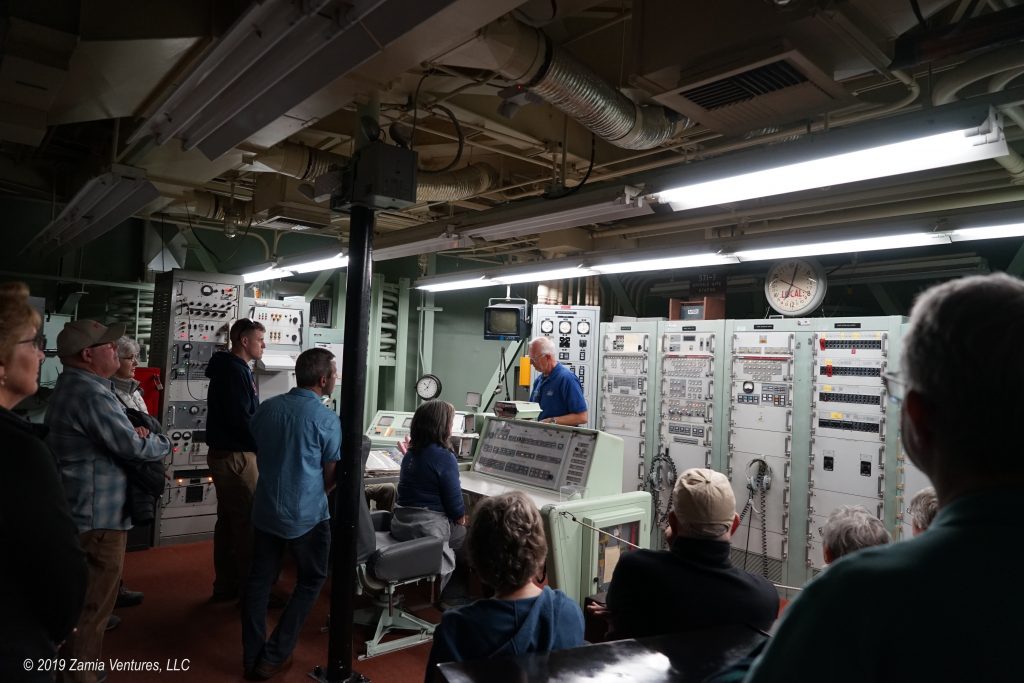

In a great leap forward in time, we also delved into technological and geopolitical history with a visit to the Titan Missile Museum located south of Tucson. From the 1960s to the 1980s, Tucson, along with Little Rock and Wichita, hosted a total of 54 missile silos holding Titan II rockets topped with the largest nuclear warheads ever deployed in the American arsenal. Each site contained one missile and its maintenance/support equipment, a hardened launch control facility, and communication equipment for receiving orders. One decommissioned site has been turned into a museum where visitors have the chance to visit the underground facilities and see the (disarmed) missile up close.

Visiting the Titan complex alone wasn’t terribly nerdy. I think most people with an interest in the Cold War would find it very interesting. What makes us super-nerds is that this is our fourth significant visit to a site focused on nuclear deterrence. The history of rocket development profiled at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, AL is very much a story about rocket technology being developed for military applications, as a specific counter to the threat posed by the USSR. In Omaha, we visited the Strategic Air Command Museum to learn about the bombers that carry our nuclear arsenal and the command structure that covers the bombers, submarine-based missiles, and ground-based missiles in silos. At the Minuteman Missile Historic Site in South Dakota, we saw the successor to the Titan II ICBM, which featured greater accuracy and carried a smaller warhead.

Each of these sites focused on different aspects of the nuclear triad, which together aimed to achieve “Peace Through Deterrence.” At the Titan Missile Museum the heavy emphasis was on the numerous fail-safes and procedures that prevented an unauthorized launch of a missile. At the Minuteman site, in contrast, there was more discussion of how the policies and procedures balanced safety with the need for launching quickly. I was particularly impressed to see that all the core design components of the facility — ranging from physical protections against a first strike to the use of codes and dual control to prevent unauthorized launch — were present from the earliest days of the nuclear weapons program and carried through into today’s Minuteman arsenal. It’s somewhat reassuring to know that, having developed weapons that could easily end all life on earth, the US and USSR have taken care to avoid ever using them.

University of Arizona Mirror Lab

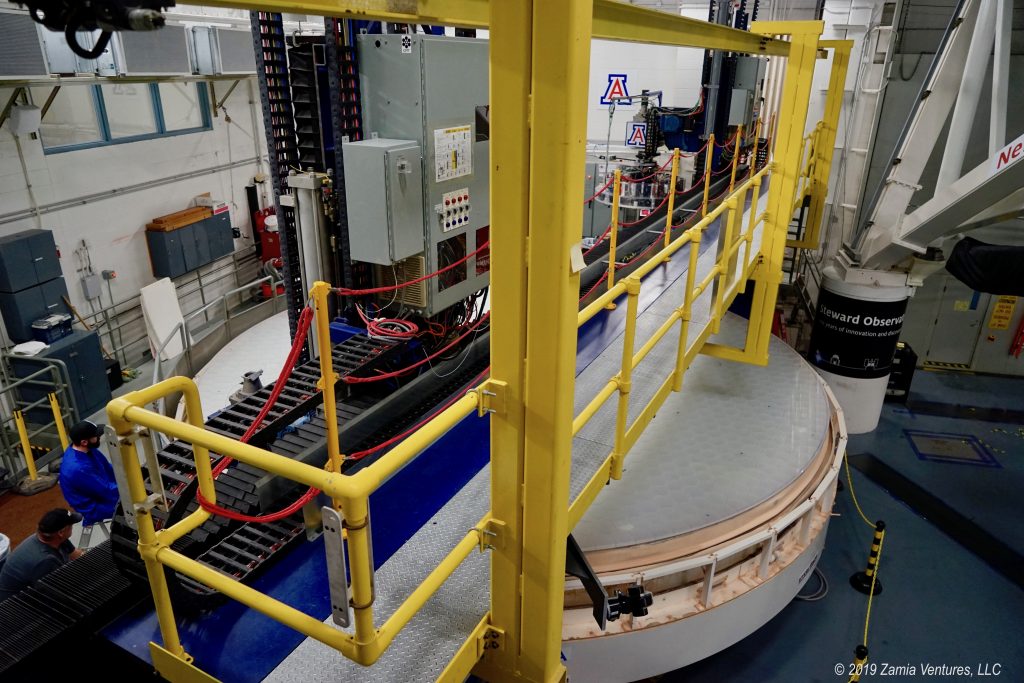

We rocketed right to the cutting edge of science with a visit to the UA Mirror Lab. The University of Arizona is a national leader in astronomical study, and is also one of the world’s best fabricators of the mirrors used in the latest and greatest telescopes being built. The original telescopes were refracting telescopes, in which light passes through a lens at the end of a tube and is focused in the eyepiece. They work much like binoculars or camera zoom lenses, and are limited in their power by the laws of physics. More powerful telescopes require huge glass lenses at the end of a very large tube to gather light, and lenses more than about 3 feet in diameter begin to sag and distort under their own weight. Having light pass through the lens also means that the faintest light gets lost. Modern telescopes are reflecting telescopes that rely on curved mirrors to gather and focus light on a sensor. The telescopes can be much larger because the light-gathering mirrors are supported from the back. They can also collect and record much dimmer light, since the light doesn’t pass through a thick glass lens.

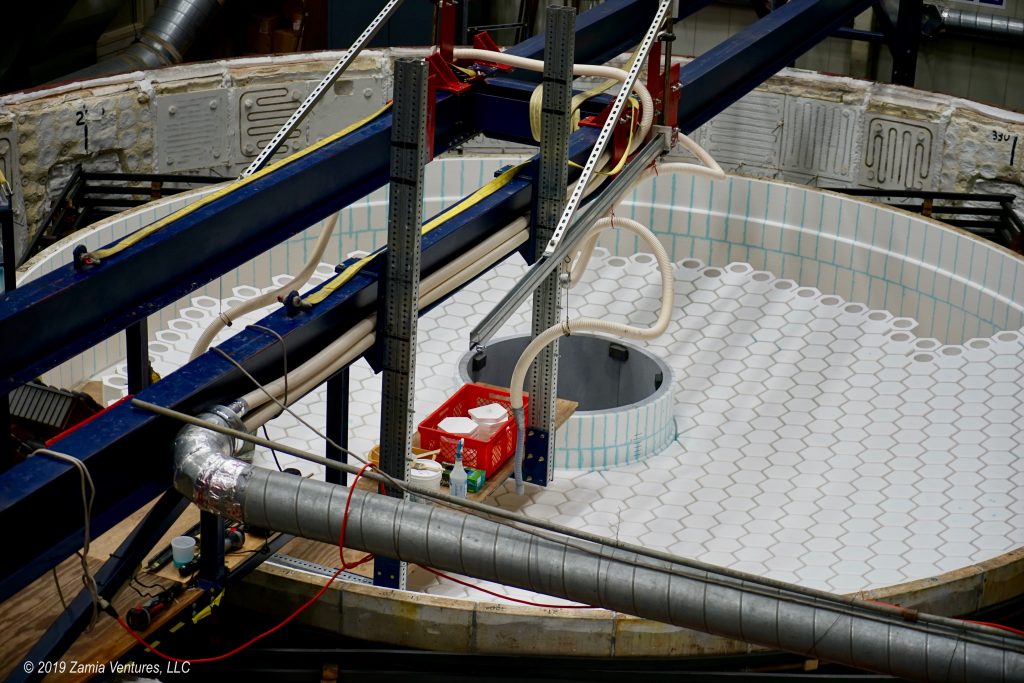

A major technical challenge for a reflecting telescope is how to fabricate a perfectly smooth mirror surface for gathering starlight, and the University of Arizona Mirror Lab is a worldwide leader in this task. Dr. Roger Angel, a member of the UA faculty, pioneered a ground-beaking process for making huge mirrors from a tough, pyrex-like glass that’s cast with hollow honeycombs on the back side of the mirror. The hollow structure means the finished product is a fraction of the weight of a solid chunk of glass, while still being rigid enough to hold its shape and durable enough to be polished into the necessary parabolic shape with incredible accuracy.

The casting process involves careful heating of special glass in a spinning furnace, prepared with the honeycomb molds, and gradually cooling the shaped glass. Just casting a single mirror takes about a year, and is far from the most time-consuming part of the process.

It would be impossible to overstate just how must precision goes into polishing the mirror surface. The required accuracy of the mirror surface is a minuscule 1/25 of the wavelength of the light it is attempting to collect, which typically equates to an accuracy of about 15-20 nanometers (less than 1.0 x 10-6 inch). For perspective, our tour guide told us that if the mirror currently being polished (an 8.4 side mirror for the Giant Magellan Telescope) were expanded to the size of the entire United States, the acceptable tolerance for imperfections in the surface would be 1 inch high. This level of accuracy is mind-boggling, but also understandable when you consider that the mirror surface will be made of aluminum applied to the glass at a thickness of less then 100 nanometers. When the aluminum coating is barely more than a few atoms thick, any defects in the underlying glass surface will result in defects on the mirror surface.

To achieve the required accuracy, the polishing process takes more than three years of constantly refining and then testing the surface. The mirror is frequently moved to an adjacent test area, where a super-precise optical measuring device identifies the remaining surface imperfections to be addressed by further polishing. The test tower is itself an engineering marvel — instead of sitting on the ground, the equipment rests on giant airbags that maintain absolute stability even when the building experiences vibrations from nearby surface or air traffic. Literally every aspect of the process used by the Mirror Lab represents an important advance in science and technology, all in the service of humans seeing further than ever before into the history of the universe.

Full disclosure: I have been a subscriber and avid reader of Discover Magazine since I was about 12. I have devoured profiles on the major telescopes currently under construction for which the lab is fabricating mirrors, including the Giant Magellan Telescope and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, both to be built in Chile. Seeing these facilities at work making the critical mirrors for exciting new telescopes was truly thrilling!

Saguaro National Park

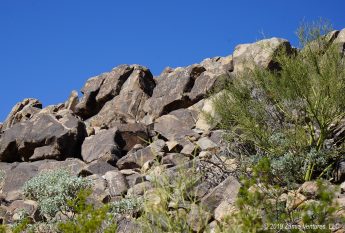

Located surprisingly close to urban areas, Saguaro National Park has two separate units on the east and west side of Tucson. This week we visited both the Rincon Mountain (east) and Tucson Mountain (west) districts, where we drove the scenic loop roads and did multiple short hikes from the loop roads. Both sections featured long desert views with encroaching suburbia in the distance and a variety of interesting hiking opportunities, including a short hike in the Tucson Mountain District to search for petroglyphs pecked onto the rocks by the Hohokam people who lived in the Sonoran Desert before the O’Odham people. The main difference between the two districts was the disparate weather we experienced. Our visit to the Rincon Mountain District was on a cool day, with clouds drifting low around the mountains, while we enjoyed brilliant blue skies the day we visited the Tucson Mountain District.

Desert Museum Redux

We also made a quick visit to the Desert Museum, made possible because we became members during our first visit. With two visits under our belt, the membership has almost paid for itself, and I know we will be back before we leave. This time instead of focusing on the charismatic megafauna, we spent a few hours learning about the creepy-crawly creatures of the desert. They might not be as cute — and some are downright terrifying — but the reptiles, amphibians, and arachnids of the desert are fascinating in their own right.

We also caught the afternoon raptor free flight show, which features a different cast of birds. This time we were awed by the elegant gray hawk, and amazed by a family of Harris’s hawks. The Harris’s hawks live in complex social groups anchored around a family unit that nests and hunts together, making them unique among raptors. The museum’s free flight program showcases a group of 5 Harris’s hawks that live as a family and soar through the crowds together in an impressive aerial ballet.

We also spent some time in the cactus garden, where the diversity of this interesting family of plants is on full display. These plants come in many different shapes and sizes, with spines ranging from horrifying knitting-needle-sized lances to virtually nonexistent. Some have a very erect growth habit, some are plump little spheres, some resemble shrubs, and there are even several vine-like creepers. Cacti are almost exclusively New World plants, and the Sonoran Desert is the perfect place to see a wide variety of them in their native environment.

Next up: art, more science, and lots of necessary maintenance tasks.

Wow, you guys are staying busy! I need a nap just reading all this. Interesting information about the missions. I only visited San Xavier del Bac and felt the same way. “Pretty place, but would like to know the real story.” A visit to Tumacacori will definitely be on the list for next time. In the meantime, I just started writing about our trip to the Mirror Lab and was intending on consulting various websites to fill in background information, but I may just link to your post instead. You did such a great job of explaining the place, I don’t see a reason for me to reinvent the wheel. Thanks for saving me tons of time! 🙂 Finally, I love you photos of the gardens.There really is such diversity in the desert, and so much unexpected beauty. I look forward to what you find next. The “Tucson to-do list” really is endless.

Visiting the artist colony of Tubac, just a few miles from Tumacacori, along with the mission ruins makes for a perfect day trip from Tucson – we definitely recommend it. Feel free to lean heavily on my description of the Mirror Lab, but be warned that there might be a quiz later! 🙂

What a great idea to join the Desert Museum since you are in Tucson for a month! We’ve been several times and never tire of it. We always get stuck in the hummingbird aviary and don’t spend much time with the slithery creatures. We need to expand our horizons. 🙂

You did a great job of explaining the relationship of the missions and the indigenous peoples. We learned the same unvarnished history in San Antonio when we explored the missions there (also NPS sites). Fascinating. Tumacacori is on our list.

The Desert Museum really is spectacular, and so well supported by the community. Having the chance to become a regular visitor and volunteer at a place like that is one of the few things that might draw us toward settling down. Thanks for the tip about the missions in San Antonio – we will be in Texas at the end of the year and will definitely check out that NPS site.