After leaving North Dakota we faced a verrrrrry long trip across the gigantic state of Montana, the 4th largest in the nation, to reach our next major destination: Glacier National Park. Eastern Montana and the northern tier of Montana are very sparsely populated (as in: plan ahead, because the next gas station could be 50+ miles away). While this makes for stress-free driving, it can also be a bit boring. Fortunately we found several interesting locations for brief stops to break up the long slog across the state.

Fort Peck Project

The first of these was the massive Fort Peck project in northeastern Montana. Started in 1933, this is one of a half dozen dams built by the Army Corps of Engineers to contain the upper Missouri River for flood control and irrigation purposes, which we first learned about in Sioux City. Fort Peck is the largest of the group by the volume of water it contains. In contrast to the high concrete dams that work best in narrow channels, the dam itself is a huge earthwork berm that is 4 miles long and barely even looks like a dam from the downstream side. It is the largest dam in the world created through hydraulic filling, which involves creating a slurry of sands and water, piping that mix into the dam area, and allowing the water to drop the sediment and flow on. Other astonishing facts: the lake is 130 miles long and the total shoreline of the lake is longer than the shoreline of the state of California.

This gigantic lake is an attraction for anglers of all types, both human and avian. We camped at the ACOE campground on the site of the dam, and I think we were the only people there without a boat or at least some minimal fishing gear. The lake (and the campground) was full of white pelicans and gulls, birds that I was surprised to see in the middle of Montana.

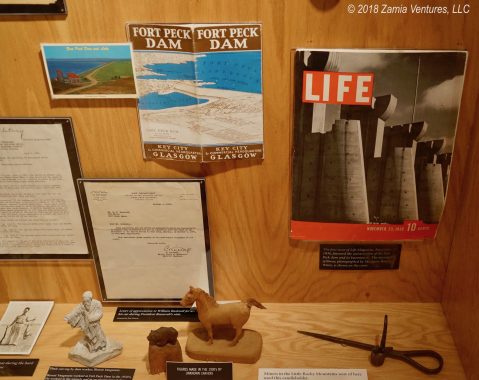

The ACOE has a very nice interpretive center on site that’s free to visit and does a great job of covering three distinct topics. One is the story of the construction of the dam, which is filled with all the usual impressive information about engineering marvels completed in an era of rudimentary machinery. It struck me that building a town from scratch to house the 10,000+ workers who ended up working on the dam in an isolated area of Montana was good practice for the ACOE’s task just a few years later of building the Secret City of Oak Ridge for the Manhattan Project. The dam project garnered sufficient popular interest to be featured on the cover of the very first issue of LIFE magazine, which was fun to see in the museum.

The museum also had a lot of good information about the wildlife and ecology of the lake itself, with huge aquariums filled with lake fish, and the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, which preserves areas along the Missouri River between the Upper Missouri River Breaks and Fort Peck Lake. Finally, the interpretive center had detailed materials about the most engaging dinosaurs. Thanks to its past as a former floodplain in the Cretaceous Era, the Hell Creek sediment layer in Montana and the Dakotas is one of the only places in the US where fossilized Tyrannosaurus Rex skeletons are found. These rich fossil beds also contain many skeletons of triceratops and other memorable prehistoric creatures. The interpretive center at Fort Peck has castings of many significant fossils, including the “Peck’s Rex” excavated just 20 miles from the dam. The mountings and presentations of the dinosaur skeletons were really top notch.

The best part of the dam visit for me was chance to take a (free) tour of the powerhouses. The dam is the site of two powerhouses that collectively host 5 hydroelectric generators producing 185 MW from the flow of the Missouri River. The water from the lake flows through four massive tunnels through the dam, each one separately capable of carrying the normal flow of the Missouri River. Two of these tunnels are topped by powerhouses that host generators spun by turbines placed in the flowing water. I was unreasonably excited to be able to actually touch one of the 30-foot-long generator shafts connecting the underwater turbines to the generators while it was spinning. So geeky, yet so cool! While this was not nearly as jaw-dropping as our visit to the Toyota plant in Kentucky, it was definitely a fun tour for these fans of industrial sites.

Upper Missouri Breaks

The westward journey continued with a stop at the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument, which preserves the area around a free-flowing section of the Missouri. It includes the famous “white cliffs” sections where the river flows through eroded badlands formations that have captured the imaginations of travelers from Lewis & Clark onward. The national monument is so remote that the only way to really explore it is by river, by taking a multiple-day canoe or kayak trip. There are several outfitters that offer guided tours in small groups of 10-15 people, paddling down the river and stopping at various campsites used by Lewis & Clark, in 3-day and 7-day trips.

However, I already live in a travel trailer, and I have zero interest in further reducing my standard of living by sleeping in a tent on the ground and eating freeze-dried or canned foods for several days. Ken has zero interest in making small talk with a group of random strangers for up to a week. Between us, we are basically a prissy misanthrope. So a multi-day paddling trip was not really an appealing option for us.

Instead, we camped along the river at the very western end of the monument, where we had the chance to watch the river, enjoy plenty of wildlife, and see many of the outfitter-led groups depart from the boat launch. For our own Missouri River paddling experience, we opted to rent a kayak from an outfitter in nearby Fort Benton and paddled a 16-mile section of the river.

One of the reasons it took the Lewis & Clark expedition 15 months to travel from St. Louis to the headwaters of the Missouri (May 1804 to August 1805) is that they were rowing the distance of 2464 miles, and the mighty Missouri is a large and fast-moving river. Even today, with the river’s flow controlled by scores of dams and lakes, the river is a formidable force, so all trips aimed at tourists are one-way only — the boats are put in at some point on the river, and paddlers get picked up by the outfitter at a designated point downstream.

I can confirm from our brief stint on the river that it is moving fast. We covered 16 miles in only 2.5 hours, and that included a near-constant challenge of dealing with swirling currents that for some reason wanted to make sure we never traveled in a straight line. Just swinging around to approach the boat ramp in Fort Benton in the upstream direction took both of us paddling at maximum strength to avoid getting swept downriver. Rowing upstream in this river would utterly destroy my will to live in about a day and a half. I have a whole new appreciation for the dedication and resilience of the men and the one extra-tough woman in the Corps of Discovery.

Since we were moving with the current, however, we didn’t have to work very hard at all once we accepted that we just wouldn’t be moving in a straight line. Instead, we could enjoy the cliffs surrounding the river and the frequent wildlife, including flocks of white pelicans and many bald eagles. Since we were not on the main river tour route, we saw exactly zero other people on the river, and few signs of human habitation other than a few ranch homes and a small herd of cows. It was delightful.

We also had the chance to experience the extremely changeable weather of the Missouri River. In just 2.5 hours, we experienced hot, sunny periods and we also got pelted by cold rain. It left us very glad that we didn’t attempt to experience three or (shudder) seven days of that. We finished up our paddle in historic Fort Benton, where we visited the interpretive center for the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument. Between watching the 20-minute film at the visitor center and spending a half-day on the river, we had our fill of this section of the Missouri, and a perfect tiny taste of the Lewis & Clark journey.

Years ago, Kevin and I did an ocean kayaking trip in the San Juan Islands (off the coast of Washington State). We kayaked 12 miles out, stayed on a small island for two nights, and then kayaked 12 miles back. It was beautiful but exhausting! We were sore for days and it didn’t help that we were sleeping in tents while out on the island. I like your plan better… just float along and try not to crash into anything. 🙂

Also, no tents involved. 🙂