Camping near Oak Ridge, Tennessee gave us the opportunity to visit one of the newest parks on the NPS menu: the Manhattan Project National Historical Park. This park is somewhat unique because it consists of three separate and far-flung sections in three different states, and also because all the locations are active sites owned by and jointly administered with the Department of Energy. All three component sections played critical roles in the development and deployment of the atomic bomb in World War II.

Los Alamos, NM is well-known as the site where scientists under the direction of Robert Oppenheimer designed the mechanism for the first atom bombs, and where bomb assembly took place. It’s near the site of the Trinity Test, the first detonation of an atomic weapon, which was needed to test the firing mechanism on the plutonium-based weapons such as the bomb that was detonated over Nagasaki. Hanford, Washington is the site where plutonium — not a naturally occurring element — was manufactured. Unfortunately the process generated large amounts of contamination in the surrounding area, so it’s not totally clear to me how this massive clean-up site serves as a National Park Service unit, but I guess we’ll find out when we eventually visit. The purpose of Oak Ridge, Tennessee was the industrial-scale production of uranium-235, an isotope of uranium which is naturally occurring but normally comprises less than 1% of mined uranium. The main job of Oak Ridge was to process tons and tons of uranium to separate the fissile isotope from the 99% of the mineral that is uranium-238, in order to provide fuel for the uranium-based weapons including the one detonated at Hiroshima.

The Oak Ridge facility can only be visited by a bus tour that leaves from the American Museum of Science and Energy, which turned out to be an incredibly interesting place to visit itself. The museum extensively covers the history of Oak Ridge and its role in the development of the atom bomb, as well as more general modern scientific information about atomic energy including explanations of radiocarbon dating, X-rays, nuclear power, different types of solar radiation, how insects can see UV light, and much more. We normally read all the interpretive displays in the museums we visit, and that just wasn’t possible at AMSE. I don’t think we’ve visited any museum with more densely-packed information, ranging from interpretive signage and photos to reproductions of important correspondence and artifacts like equipment and uniforms. There was even interpretive signage in the restrooms!

The story of the development of Oak Ridge was extremely interesting in several ways. First and foremost is the speed at which it was created. The Manhattan Project was directed by the Army Corps of Engineers, and the ACOE selected the Oak Ridge site thanks to its remoteness, small population, access to water and electricity from a nearby TVA dam and hydroelectric facility, and multiple valleys separated by ridges that provided natural security and privacy. The site was selected in late 1942, 90 square miles of property were acquired through eminent domain and fenced in, construction began in April 1943, and the atomic bombs were dropped in August 1945. Within 2.5 years, Oak Ridge was transformed from a sparsely populated rural area to a factory town with a population of 75,000 people, complete with housing, schools, a bus system, churches, supermarkets, and entertainment and recreation facilities. The property contained not just one but three different industrial-scale uranium separation plants, each employing a different method of isotope separation — gaseous diffusion at K-25, liquid thermal diffusion at S-50, and electromagnetic via calutron at Y-12. At the time it was constructed, K-25 was the largest building in the world under a single roof; it had more than 35 acres of interior space. In many cases these massive plants scaled up technology that was mostly theoretical and barely tested, so the builders were essentially inventing the methods and procedures while the plants were being built. The ACOE was also very creative in procuring the materials required. Because of the war-time shortage of copper, over 14,000 tons of silver were borrowed from the US Treasury and used to make electrical wiring and components to serve the energy-hungry calutrons. Once operational, all these plants operated around the clock, three shifts per day. The level of planning, procurement, logistics, employee recruiting, and pure construction work required to create all of this in a few short years was really mind-blowing.

The second fascinating aspect of the Secret City was that it was, well, secret. The entire city and the production facilities were completed fenced in, with all persons over the age of 12 required to wear ID badges at all times. When residents left the compound to go to Knoxville or elsewhere, they didn’t discuss what went on behind the fences. Of course, the vast majority of the workers had no idea what they were working on — they were simply trained to monitor certain dials or record readings from certain instruments. In fact, the entire Manhattan Project was so secret that Harry Truman, Vice President of the United States, did not know about its existence until after he became president in April 1945, just months before he would be faced with the decision of whether to order the use of a nuclear weapon in war. So for all you conspiracy theorists out there looking for an example of a massive government project employing tens of thousands of people to develop advanced weaponry, known only to a few people at the very highest levels of government: you’re welcome. The world first learned about Oak Ridge — which was then the sixth-largest city in Tennessee, but appeared on no maps — from a press release issued by the Army Corps just days after the Little Boy bomb fueled by Oak Ridge uranium was detonated at Hiroshima. Today this sort of secrecy would be impossible (at least on the surface of the earth) because of readily available satellite photography, which makes the whole thing seem even more exotic and surprising.

The bus tour travels through several of the valleys that hosted the large production sites, though currently there is not that much to see in several of the locations. A stop that focuses on the communities that were displaced by the establishment of Oak Ridge is the New Bethel Church, dating to the 19th century and abandoned in 1942 but still standing despite all the activity in the surrounding area.

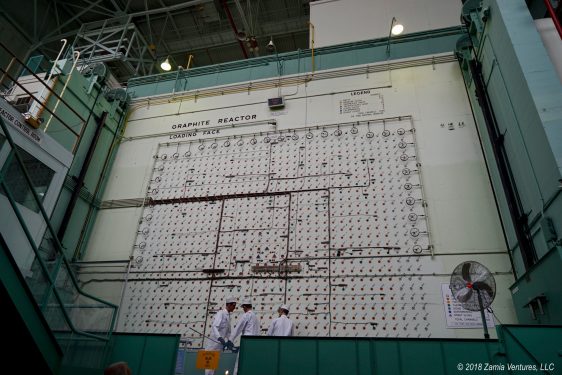

For us, the highlight of the bus tour was the stop at the X-10 graphite reactor. X-10 was the fourth major active site at Oak Ridge, and the only one not focused on uranium enrichment. Instead, X-10 contained a nuclear reactor and chemical separation facilities to produce plutonium that served as a pilot for the much larger plant built at Hanford. X-10 featured an air-cooled, graphite-moderated reactor modeled on the version pioneered in Chicago by Enrico Fermi; it was the world’s second artificial nuclear reactor. Being able to walk around the loading face of the reactor and into the control room was fantastic. It really brought home that atomic energy was harnessed using surprisingly basic tools and instruments, though of course it was all incredibly cutting-edge for its time.

We learned a bit about the post-war activities of the various components of the site as well. Uranium enrichment at Oak Ridge continues, mostly to supply the fuel for the Navy’s nuclear-powered ships. Oak Ridge facilities have also helped get rid of weapons-grade uranium from decommissioned bombs from the arsenals of both the US and former USSR, which happens by “downblending” the highly concentrated U-235 with U-238 to create a mixture suitable for commercial power plants. The advanced atomic research work of X-10 has been continued by what is now the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the largest national laboratory within the Department of Energy. The cool tools on site include the Titan supercomputer and several facilities for research using neutrons (the Spallation Neutron Source and the High Flux Isotope Reactor). It’s great to see our tax dollars at work in the critical area of advancing basic science!

The visit also gave us a chance to think about the ethics of building and deploying a nuclear weapon. Even before the Manhattan Project commenced, scientists and political leaders appreciated the terrible power that atomic weapons would deliver. But there wasn’t really much choice but to proceed. Nuclear fission was discovered in Germany in 1938. Germany was working on exploiting this physical phenomenon for a weapon, in its own version of the Manhattan Project. Germany was regularly demonstrating its technological expertise with weapons like the V-2 rocket. Losing the race to build an atomic weapon would almost certainly mean American defeat in World War II. The decision to greenlight the Manhattan Project seems inevitable, even though attempting to build an atomic bomb would require a massive investment with no certainty of success. It was the ultimate “Go big or go home” moment.

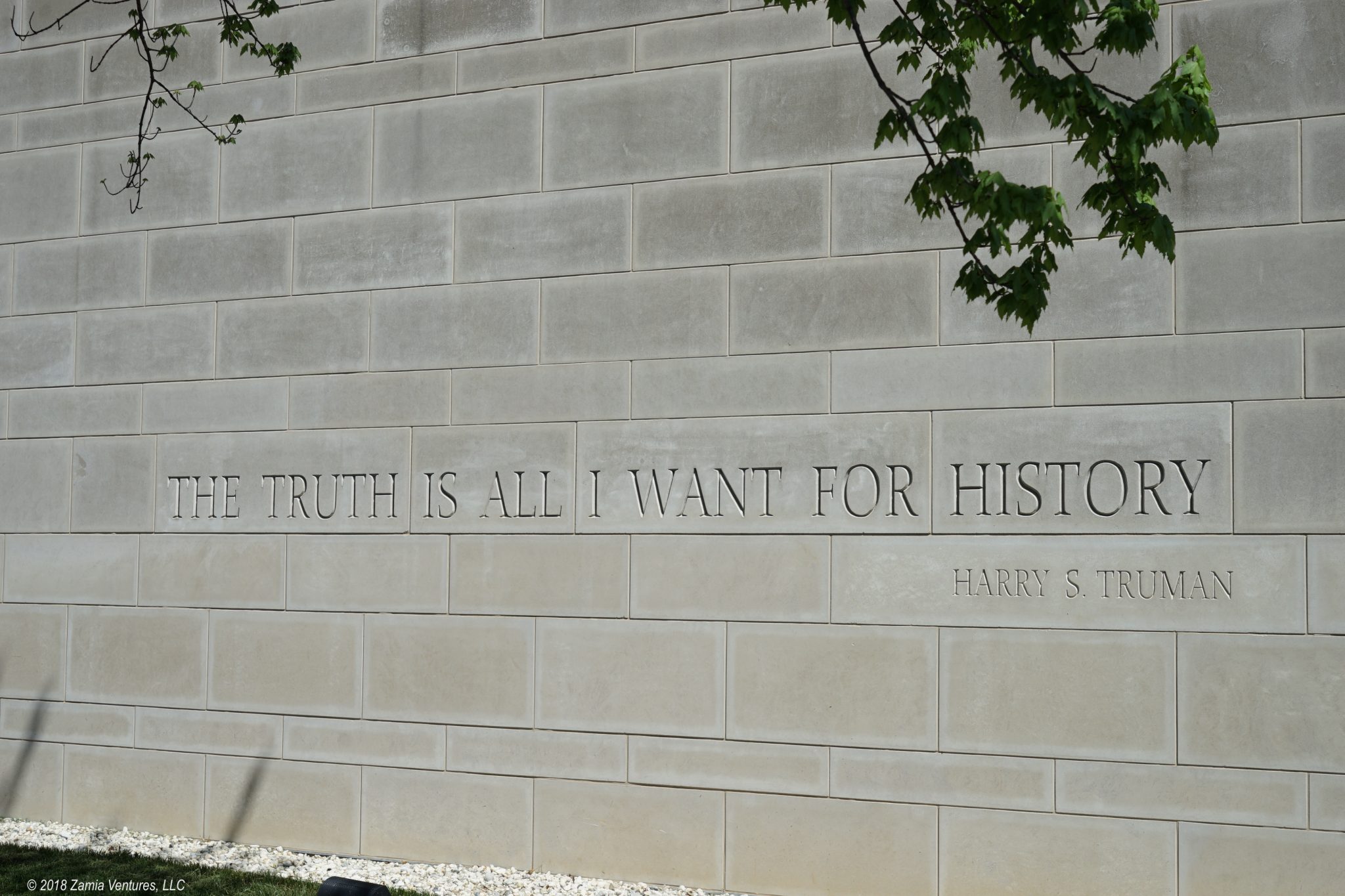

The difficult decision to actually use the weapon, once it was developed, is one that we’ll be exploring more when we visit the Harry Truman library and historic site in Independence, Missouri. For now, we’re headed to the mountains for a week of hiking, with our brains full of scientific information thanks to this great museum and NPS site.

5 thoughts on “Entering the Atomic Age at Manhattan Project NHP”