Our 2022 summer sojourn finished up with several days of driving on rural roads punctuated by two short stops in Georgia. And our stops provided a fitting bookend to a summer that started with a very challenging and thought-provoking stop in Montgomery.

Hard Labor Creek State Park

On our way south from Asheville, we made a brief stop at Hard Labor Creek State Park. We got this idea from our friends over at Raven and Chickadee, and because we are entirely unoriginal we even occupied the same site they enjoyed last year. During our one day in the park we explored the relatively short hiking trail system that connects to the campground, and relaxed in the enormous, shaded outdoor patio area on the site while basking in pleasant temperatures and low humidity.

Andersonville National Historic Site

Our final stop in Georgia brought us to two more National Park Service units located within 20 miles of each other but dealing with very different times. The Andersonville National Historic Site includes the former site of the notorious Andersonville prison camp, a place where more than 45,000 US prisoners of war were held captive during just 14 months of the Civil War. The site was selected because it was on a rail line but far from the front lines, and offered a large area that could be fenced. The Confederate government forced enslaved people to build a wooden stockade surrounding about 16.5 acres (later expanded to 26.5 acres) that had a murky stream running through it as a “water supply” and did little else.

US POWs arrived on railcars and were herded through the gates like cattle and then left up to their own devices. Prisoners were responsible for creating their own shelters out of mud, sticks, and random bits of fabric, while the Confederate decision to place only enlisted men in this camp meant there was no command structure inside the walls. Violent gangs ruled the place, and prisoners bartered anything of value in a desperate attempt to obtain rations. The overcrowding was extreme; a place designed to hold 10,000 men had swelled to 33,000 men by August 1864 and constituted the 5th largest “city” in the Confederacy at the time. It’s no surprise that malnutrition and disease led to the deaths of nearly 13,000 prisoners, a shocking 28% death rate among soldiers who were away from active combat. Multiple survivors described it as a hell on earth, which seems about right.

Today little remains of the original site. A partial stockade wall has been reconstructed for demonstration purposes, and the grounds are dotted with elaborate monuments erected by various states in honor of their dead soldiers along with archaeological survey markers for items like wells dug by the prisoners (with spoons and plates!!) in an effort to obtain clean water. Mostly the site is a vast grassy area that’s simply overwhelming in scale.

The National Park Service uses this vivid example of the deprivation that POWs can endure as the starting point for the National Prisoner of War Museum, located in the visitor center at Andersonville. The museum tells the story of American POWs from the Revolution to the present day, but instead of going in purely chronological order the museum is arranged thematically. Different sections explore topics like “entertainment while imprisoned” and “escape attempts” while tying together the experiences of American POWs in places as diverse as England, the Confederacy, Germany, Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq. While we thought the effort was admirable, we ended up finding them museum to be a bit disjointed and confusing. Massive changes in technology have meant that in different conflicts American soldiers have faced very different risks in battle, different likelihoods of being captured, and different challenges as POWs. The museum struggled to tie them all together, in our opinion.

We thought the most moving part of Andersonville was the national cemetery. The 13,000 people who died while the prison camp was open were buried side by side in trenches with simple numbered wooden stakes to mark their graves. A US prisoner named Dorance Atwater who was conscripted into recordkeeping duties secretly kept his own copy of the death records, and returned to Andersonville in the summer of 1865 with Clara Barton, who later founded the American Red Cross. These two connected the numbered stakes with the names of the deceased on Atwater’s smuggled list, providing closure to their families and installing permanent markers for the dead. Remarkably, despite the massive number and frequency of deaths, fewer than 500 of the POWs ended up marked as “unknown US soldier.” The burial ground was further expanded when US soldiers who had died in the conflict in battles around Georgia were moved from hasty battlefield graves to the new national cemetery, and unfortunately many more of them were unknowns. The sheer volume of the graves, accompanied by even more state monuments, made for a somber experience.

Meanwhile the adjacent town of Andersonville illustrates some of the conflicts that continue to divide us. We spent a bit of time around town because we camped at the city-owned RV park in the heart of town and checked in at the Visitor Center / Little Drummer Boy Museum a block away. It’s impossible to miss that the town is trading on its Civil War history and gives equal weight to both the United States and Confederate sides. Despite the prison being an enormous monument to US POWs, there are plenty of Stars and Bars flags around. And it’s impossible to miss the huge monument in the middle of the main street to Captain Henry Wirz, the Confederate commander of Andersonville. He was hanged in 1865 for war crimes, largely as a result of the outrage over the conditions in the prison camp.

To be fair, it’s unclear what Wirz could have done differently. In 1864 Confederate troops were also dying in large numbers from malnutrition and disease, and the overcrowding of the prison was due to policy decisions beyond his control. There is no question that he was used as a scapegoat while people like Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis spent their later years writing memoirs, going on speaking tours, and serving as college presidents. But the giant monument to Wirz in Andersonville was erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy specifically in response to the various state monuments in the prison camp and cemetery, and the petulant tone of the inscription mirrors the general unwillingness of the south to let go of its dreams of being a separate, white supremacist country. I will simply note that I have visited Auschwitz, and I did not notice any swastika flags or monuments to Adolf Eichmann there.

Jimmy Carter National Historic Park

Andersonville is just 20 miles from Plains, GA, so with a very short drive we made a visit to the hometown (and virtually lifelong residence) of our 39th president to check out the Jimmy Carter National Historic Park. The park has three components, and because Plains is absolutely tiny we were able to explore all three in one morning. The impressive building of the former Plains High School (actually grades 1-11 (!)), from which Jimmy and Rosalynn both graduated, is the park’s visitor center and main interpretive site. At the school, we got a rare taste of how the National Park Service can tell the story of contemporary history, instead of trying to bring to life ancient cultures or millennia-long geological processes. The park film is narrated by Charles Kuralt and features plenty of footage of Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter along with campaign volunteers, friends, and neighbors; no historical re-enactors are needed here.

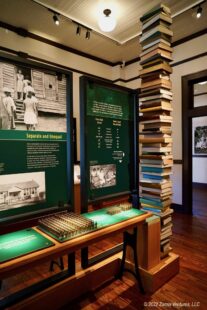

But while the park’s subjects are still living, much has changed in their lifetimes and the park service doesn’t ignore that segregation was alive and well during their youth and early adulthood. The school Jimmy and Rosalynn attended was an impressive edifice open only to white children, while their Black peers were consigned to a one-room schoolhouse elsewhere in the county. Plains High School didn’t desegregate until 1970 (!!) and the interpretive center does a good job of highlighting the disparities in resources between the segregated schools. It also nicely summarizes three main phases of Carter’s life: his youth in Plains, his political career as governor and president, and his very busy life after the presidency.

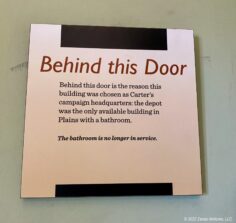

The second component of the park can be found just a block away from the visitor center: the downtown train depot that served as Carter’s presidential campaign headquarters. From here, Rosalynn organized scores of friends and neighbors into the “Peanut Brigade” that hit the campaign trail on behalf of their hometown candidate. And from here, a huge group of local supporters boarded an 18-car train to Washington (dubbed the “Peanut Special”) to attend the inauguration in Washington. This was the weakest of the three components, but I made up for it by trying the famous peanut butter ice cream at one of the stores across the street.

The third and final stop was at Jimmy Carter’s boyhood home, located 3.5 miles west of downtown Plains. The farm where he lived throughout his youth is maintained by the NPS as a living farm, complete with demonstration gardens and livestock, and visitors can tour the modest home as well as the various outbuildings. Interestingly, the farm is located in an African-American community, and the Carter family was one of two white families in the area. The close relationship between young Jimmy and his father’s Black farm supervisor is explored at some length, and credited with Carter’s later efforts to desegregate Georgia public schools and his appointment of the first Black woman to the cabinet and the nation’s first Black UN ambassador.

We knew that Jimmy Carter famously came from a small peanut farming town in Georgia, but visiting Plains really brought that point home. The place is incredibly small; the entire commercial district consists of about 10 buildings in a single row facing the railroad tracks, surrounded by views of peanut silos. The rural area where we live feels like a booming metropolis in comparison. The Carters still live in Plains, and — in what must be a rarity for former US Presidents — their current home is identified on the park map. It’s marked as “not open to the public,” of course, but we drove right by it on our way out to the farm and back. Other than having a modest perimeter fence and a small guard shack at the end of the driveway, the Carter home looks like most of the others in the neighborhood. The longstanding connection of the Carter family to Plains was reminiscent of Gerald Ford’s lifelong love for Grand Rapids, MI, creating an interesting symmetry between these two men who competed for the presidency in 1976.

And that’s a wrap!

And with that, we returned home to St. George Island. I’ll have at least one more post summarizing our travels in facts and figures and reflecting on the summer.

Thanks for the very interesting and thought-provoking tour of Andersonville and the historic site there. I saw a photo of a prisoner from the Andersonville POW camp when we were at the Lincoln Museum that honestly, I wish I could unsee. I don’t know how anyone survived those horrific conditions. Obviously, a large number of them didn’t. Your photo of the cemetery is sobering. And your description of life in the POW camp…digging a well with a plate and spoon?? How is that even possible?

I find it disturbing to find monuments to the Confederacy and Confederate flags in so many places…as you said so perfectly, ever-present reminders of the unwillingness of the South to let go of its dreams of being a separate, white supremacist country (even though the argument is often made that they’re simply honoring their past). But you know what’s even more disturbing? Confederate flags in Wisconsin and Michigan. WTH?? That, clearly, can’t be rationalized as anything except white supremacist terrorism.

Anyway, on a happier note, I loved your tour of Jimmy Carter’s hometown. I just can’t get over the fact that after leaving the Whitehouse, they returned to Plains. That certainly lends credence to them being down-to-earth, modest people. And yes, Plains makes St. George/Eastpoint/Apalachicola look positively fabulous!

Okay, this has been bothering me ever since I posted it and couldn’t edit it, so I’m fixing it now.

White House. Not Whitehouse. LOL.

Enjoy home! Eat more shrimp!

You are such a perfectionist. Live a little! Embrace new ways of spelling! 🙂

I know the photo you are referring to; several similar ones are featured in the park’s introductory film. The photos were accompanied by narration quoting survivors, and it was a gruesome introduction to the horrors of Andersonville. The fact that over a quarter of the prisoners died is a testament to how terrible the conditions were, but perhaps the more surprising fact is that almost three-quarters lived! The resilience of human beings is remarkable.

Nostalgia for the Confederacy is something we’ve been thinking about a lot lately since it came up so frequently during our travels this summer. I would be a lot more sympathetic to the views about “honoring heritage” if the people (or monuments) saying that would also acknowledge that the heritage included an attempt to exit the United States in order to establish a new country built on a foundation of racist exploitation. Most Confederate monuments I’ve seen — and living in the south my entire life I’ve seen a lot!! — have inscriptions that portray Confederate leaders as saint-like figures who were essentially blameless victims. It’s ridiculous.

On the Carters, I was also pretty surprised that they returned to Plains after traveling the world (first while he was in the Navy, then as president). After seeing it in person, my surprise turned into complete astonishment. It’s hard to communicate just how small the place is.

Obviously, there is some question about how good of a president Jimmy Carter was, but no one can question that he is and always has been a good human being. He has truly walked the walk and, as we seem to be surrounded by charlatans using their bastardized views of religion to spread hate every which way, it’s nice to know there are people like the Carters actually living up to the ideals of Christianity.

Also, I agree with what you and Laurel said re the Confederate symbols. I’m beyond tired of the “heritage” b.s. Nirvana lasted longer than the Confederacy. It’s not about “heritage,” it’s about people being racist dicks. Give me a break.

And, on that note, in some sad ways, your summer trip came full circle. Starting in Alabama with people fighting racism and ending in Plains, with people still celebrating racism. Maybe some day we can all move beyond this, once and for all. It’s nice to think about, anyway.

Our visit to the Carter Historic Park really highlighted Jimmy and Rosalynn’s fundamental decency and humility, which is always a pleasure to find. It echoed our visit to the Ford Presidential Museum, which provided another example of a person who had great integrity and personal character even if the presidency wasn’t a complete success. It raises the troubling question of whether good people can even succeed in politics…. I’m not sure.

That’s just one of the many threads that seemed to weave through the entire summer. Visiting more urban areas, museums, and historic sites instead of just wall-to-wall nature-oriented parks gave us a different experience this summer and we’re still reflecting on our impressions from many thought-provoking places.

Shannon, the other day Henry and I went to the Crawford W. Long Museum in Jefferson, which is only about 20 minutes from us. Who knew some local guy started using ether for surgery in 1842? And his brother and he had a pharmacy in Athens where the arches are now. Our next day trip will be to Dahlonega to see the gold mine and visit the wineries.

That sounds like a very fun visit – it’s amazing how many quirky, interesting little museums are scattered around the country. The gold mine and wineries sound like great places to visit also!