While we are thrilled to be back on the road, we knew that our first stop of the summer would also be one of the toughest. Montgomery, Alabama was critical in igniting the mid-20th century civil rights movement thanks to the 1956 Montgomery bus boycott that brought national attention to a charismatic 26-year old local minister named Martin Luther King, Jr. Now Montgomery is home to an impressive array of museums and monuments that document significant people and events in America’s long and unfinished struggle towards racial justice.

The Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice

The Legacy Museum has been on my radar since it opened to great acclaim in late April 2018, just weeks after we first traveled through the area. The museum provides rich analysis of four phases of racial injustice in America: enslavement, post-Civil War racial violence (lynchings), segregation/Jim Crow, and mass incarceration. Unlike a typical history museum, the Legacy Museum shows no historical artifacts whatsoever. Instead the information is shared through a combination of original artwork, films, data visualization, and reproductions of primary source material like newspapers, photographs, and first-person accounts. The combination is powerful.

Readers, you must settle for my written descriptions of the museum because unfortunately photos are not allowed inside. The entry to the museum is through a room filled with sculptured heads and torsos representing some of the people trafficked to the Americas in the Transatlantic slave trade. Their individual expressions of grief and anguish really brought home the human cost of 12 million people kidnapped from Africa, while the data visualizations of shipping routes and increasing population tallies showed how the Americas were shaped over time by this massive dislocation. Similarly, searing first person audio narrations of families being separated when a spouse, child, or sibling was sold — a calamity that half of all enslaved Americans experienced as the domestic slave trade boomed — were reinforced by a huge wall reproducing dozens of newspaper advertisements taken out after the Civil War by family members desperate to reunite with their loved ones. The section on lynching is anchored by a very strong piece that unifies art, visual information, and community engagement under the theory that “there can be no reconciliation and healing without remembering the past.” Members of communities where documented lynchings occurred have collected soil from the murder sites in 5-gallon glass jars, and the Legacy Museum has an enormous two-sided wall displaying these soil collections. Seeing a floor to ceiling display of dramatically-lit, multi-hued jars containing everything from rich red clay to light sands to dark loam, each labelled with a victim’s name and date of death, is a powerful statement that racial violence affected people in many different places and environments. The throughline of American racial injustice is carried seamlessly into the modern era with detailed sections about segregation, the Montgomery bus boycott and subsequent civil rights actions, and contemporary racial disparities in policing, prosecution, and sentencing. The museum is thorough, thought-provoking, well-documented, and utterly heartbreaking.

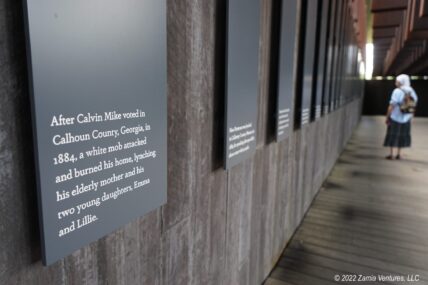

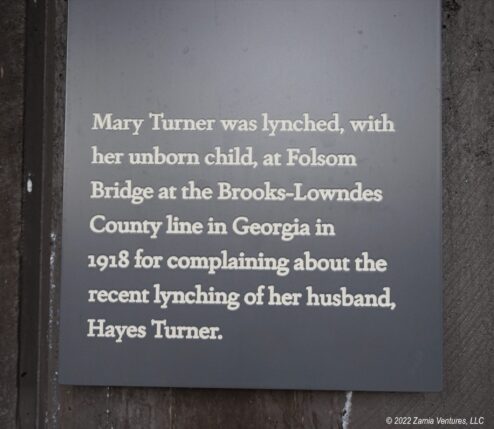

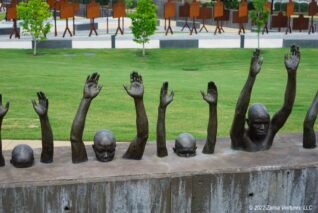

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a companion project of the Equal Justice Institute, is the result of a years-long effort to document the racially-motivated murders of Black Americans between 1877 and 1950. Known informally as the Lynching Memorial, it includes names and dates of death inscribed on huge metal boxes that are hung from the ceiling, one for each county. Visitors start at eye level with the inscribed pieces and then proceed down a ramp to a position below the hanging pieces. The memorial includes some appalling captions explaining why some of the victims were lynched, along with inspirational quotes from Black writers. The design of the memorial is haunting. By the time visitors reach the lowest part of the memorial, as seen at the top of this post, all those hanging boxes are very reminiscent of the “strange fruit” of southern trees that Billie Holiday vividly denounced. After going through the main memorial, visitors have a chance to examine a field of duplicate boxes laying on the ground and arranged alphabetically by state and county (find your hometown and be sad!), where it becomes quite clear that they are the size and shape of coffins. The sobering atmosphere is enhanced by several groups of sculptures depicting the agony of enslavement, the persistence of the women who led the Montgomery bus boycott, and the fear induced by police violence. While not exactly uplifting, the memorial provides a valuable space for reflection.

Rosa Parks Museum

Rosa Parks is known to most school children as a seamstress who kicked off the civil rights movement by refusing to give up her seat on a segregated city bus to a white person. Much more than merely a lady who had tired feet, Rosa Parks was actually an experienced civil rights activist who had attended a workshop at the Highlander Folk School and served as the secretary of the local chapter of the NAACP. Because she was perfectly-positioned, her 1956 arrest sparked a boycott of city buses that lasted over a year and served as proof of concept for non-violent, coordinated action to end segregation. It was truly pivotal in initiating the modern civil rights movement.

The Rosa Parks Museum uses engaging audio and video, including items like a full-size replica bus with video projected onto the windows depicting the key event, to vividly tell the story of the boycott. Like the Legacy Museum, no photos are allowed inside. Unlike the Legacy Museum, the Rosa Parks Museum is actually part of the archives of the Troy University library, so there is a wide range of original documents on display: historic newspapers with coverage of the boycott, correspondence with national civil rights groups, police reports about various events that occurred during the boycott, and the bank account records of the Montgomery Improvement Association, the group that emerged to coordinate the boycott and had elected MLK as its leader.

The museum highlighted the key roles played by two women activists in initiating the boycott: Rosa Parks and Virginia Durr, a white woman committed to equality and married to an influential local lawyer. We also learned about the logistics of maintaining the boycott for such an extended period of time, including the Montgomery Improvement Association’s purchase of numerous station wagons to run an elaborate transportation network so boycotters could still get to work. It was interesting to see how the white supremacist establishment used boring administrative tools to try to shut down the boycott, such as having white insurance agents cancel the auto insurance on the MIA’s vehicles. The museum also explored MLK’s personal, faith-based acceptance of the risks of activism, which proved necessary when his house was bombed during the campaign (fortunately with no injuries).

The boycott ultimately ended when the U.S. Supreme Court determined that state and local laws requiring segregated city buses were unconstitutional. But the bus boycott was only the beginning of the civil rights movement, and the museum effectively connected the events in Montgomery to the establishment and work of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and other organizations that organized numerous nonviolent protests over the next several decades. The museum was a relatively small but worthwhile stop, and I also enjoyed seeing several politically-relevant murals on the same block as the museum.

Museum of Alabama

We also stopped by the free public Museum of Alabama at the Alabama Department of Archives and History. Similar to the Museum of Florida History that we visited in Tallahassee in 2018, this museum starts with a description of the geological history of the state and then covers the breadth of its human history. One room has a comprehensive look at pre-Columbian inhabitants from the Paleothic (including Russell Cave, which we visited before) through the widespread Mississippian mound-builder culture, with plenty of artifacts from every period. The main section focuses on the colonial era through the present day.

My main take-away was the astonishing speed at which Alabama developed, and then subsequently swung from high to low and back again. In 1800, Alabama was almost entirely inhabited by members of the Creek tribes who were the last remnants of the various Mississippian groups. It was surrounded by foreign territory including Spanish Florida to the south, French Louisiana to the west, and newly independent American states to the north and east. Within a generation the Creeks had been almost completely destroyed thanks to Andrew Jackson, who struck the final blow in 1814 at Horseshoe Bend (which we visited). Settlers rushed west and south from Georgia and the Carolinas to take advantage of newly available land, and in the blink of an eye a huge agricultural economy was built. By 1830 there were 300,000 residents and by 1860 there were almost a million Alabamians.

The museum presented information and artifacts to tell the stories of three very different groups who were part of this meteoric rise in population: poor subsistence farmers (“yeomen”), enslaved African Americans who made up nearly half the population, and the small but extremely wealthy and powerful planter class. The Civil War led to the complete collapse of the slavery-based economy, only to see the state rise in the late 19th century to be the most industrialized state in the south thanks to cotton mills, lumber mills, and the happenstance of geology: rich deposits of clay and metal ores that were perfect for making iron and brick. The Depression was yet another catastrophe, followed by the social upheavals of the civil rights movement.

The museum didn’t whitewash the darker elements of Alabama’s past, with coverage of slavery, poverty, the Klan, and more. But it addressed these topics in a far more detached and clinical way than the other museums we visited. This conventional approach was accurate and reasonably comprehensive, but lacked the emotional and moral force of the other places.

More Montgomery Sightseeing

We also made brief visits to numerous other locations around Montgomery, including:

- Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, the first church that MLK led as a young pastor and where he first made his name as a civil rights activist.

- The Civil Rights Memorial designed by Maya Lin and hosted on the grounds of the Southern Poverty Law Center. The sleek black table-like fountain commemorates significant events in the civil rights struggle from the 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka through the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. The design is suspiciously similar to the Women’s Table that Lin created to commemorate 20 years (not a typo!) of coeducation at Yale in 1991. But I guess if you have a good idea there’s nothing wrong with repeating it as often as possible (see also: Bob Seger’s lyrics to “Night Moves”).

- The Alabama State Capitol Building, which has generally been restored to the condition that existed when it was the site of the first meeting of the seven states that established the breakaway Confederate States of America and adopted the first Confederate constitution in February 1861. As Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens pointed out in his Cornerstone Speech the following month with respect to the rebel nation: “[I]ts corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.” So it comes as no great surprise that this is the same Capitol where in 1963, a century after the Emancipation Proclamation, newly elected governor George Wallace announced in his inaugural address his famous commitment to “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” To reinforce the point about institutional commitment to white supremacy, the Capitol grounds also feature a gigantic Confederate monument and a separate statue of Jefferson Davis.

- The first Confederate White House, where Jefferson Davis and his family lived until the Confederate capital was relocated to Richmond.

Selma to Montgomery Trail

As if all that were not enough, we also swung by one of the three interpretive centers for the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail. By 1965, the fight for civil rights had moved beyond just challenges to legalized segregation and focused on a critical topic: voting rights. Although technically the 15th Amendment gave the formerly enslaved the vote, in the Jim Crow South a variety of barriers like bogus tests and poll taxes made it difficult or impossible for Black people to register to vote. The situation was particularly dire in rural counties like those stretching between Selma and Montgomery, where Black people represented a majority of the population but were generally kept in complete economic and political subjugation as sharecroppers who were wholly dependent on plantation owners. For example, in Lowndes County, where this interpretive center is located, just over 80 white families owned 96% of the land in the county while over 80% of the population was Black.

Coming nearly a decade after the Montgomery bus boycott, the Selma to Montgomery march involved hundreds of marchers peacefully walking 54 miles in an effort to secure their right to the ballot. The extreme brutality of police attacks in the first several days (including Bloody Sunday) riveted the nation and led President Lyndon Johnson to call out the National Guard to protect the marchers. Ultimately, 25,000 people marched into Montgomery to demand their constitutional rights. While the Alabama government was as uncooperative as ever, the march caused LBJ to push for adoption of the Voting Rights Act, providing affirmative guarantees of voting rights for all citizens.

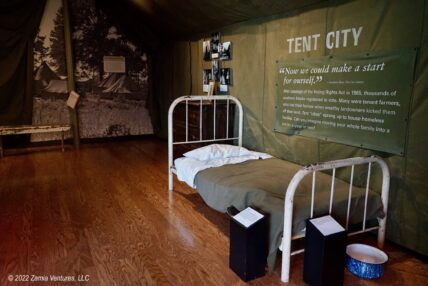

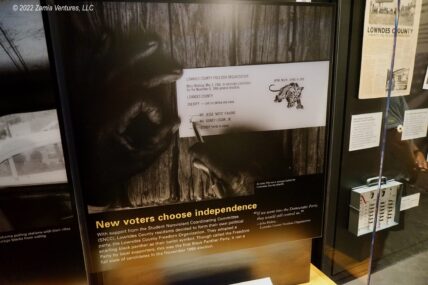

The problems didn’t magically end with the signing of a bill, however. Black citizens who actually registered to vote found themselves evicted from their leased land in large numbers. SNCC set up tent cities where these families could live, sometimes for over a year, while SNCC helped them get on their feet with funds to purchase their own lands to farm. One of these encampments covered 5 acres and was located next to the Lowndes Interpretive Center. My favorite fun fact from this visit relates to the efforts by SNCC volunteers to register voters under the new Voting Rights Act. While local leaders were grateful to LBJ and other Democrats in the Congress who passed the Voting Rights Act, they had no interest in joining George Wallace’s Democratic Party which had as its logo a white rooster. So instead they formed the Lowndes County Freedom Organization to nominate Black candidates, and created a logo featuring a black panther. Local organizing work in this poor, rural county is where the Black Panther Party got the idea for its name and logo. As usual, the NPS interpretive center does a great job of showing artifacts along with signage providing context for the site.

For Further Reading

Ken and I have both been reading Let the Trumpet Sound: A Life of Martin Luther King, Jr. by Stephen Oates, which greatly improved our appreciation of the important people and events of the 20th century civil rights movement. It’s pretty amazing just how little we previously knew about this pivotal part of American history. This book is quite readable and engaging, but also delivers a thorough explication of King’s intellectual, theological, and moral reasoning behind his focus on non-violent resistance.

An extremely deep (and heavily footnoted) dive into the broad range of theoretical, historical, scientific, and philosophical arguments for white supremacy advanced throughout American history can be found in Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America by Ibram X. Kendi. I got a lot out of it when I read it for a book club last year, but don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Where We Stayed

The leafy lakeside Catoma Campground at the Army Corps of Engineers Gunter Hill Campground lived up to all the great reviews. Our full hookup waterfront site (#13) was enormous, private and surrounded by tall trees.

Unfortunately, because our visit coincided with an enormous heat wave over much of the country, we experienced daily heat index numbers well above 100 degrees. Thanks to our brand new air conditioner we spent a lot of time indoors trying to avoid heat stroke and couldn’t really enjoy the scenery as much as we would have liked. We did have the pleasure of having our stay overlap with our friends Eric and Laurel, and we shared one sweaty but enjoyable happy hour.

Next up: we head north to Huntsville, where I look forward to having much less depressing material to share.

Great post and commentary, and so timely with Juneteenth around the corner! Thanks for the education, and we wish you cooler temps as you continue your travels.

Thank you for the kind words and the good wishes. I fear the weather gods will not be granting your wish soon enough, but eventually we will get far enough north to evade the heat. Even though we do have a new air conditioner, we’d really prefer not to run it all the time.

Shannon, this is a fantastic post. I think when I write about Montgomery I’m just going to refer people to your post, because you’ve done a far better job than I ever could do. We’re still talking about and absorbing all that we experienced. Although we’ve been to the Civil Rights Museum in Memphis (and highly recommend it), the Legacy Museum is unique in helping me understand how slavery has not ended, it has just evolved. Anyone who thinks we don’t owe reparations to the Black people of this nation needs to visit the Legacy Museum. As Martin Luther King said, you can’t tell someone to “pull themselves up by their bootstraps” when they have no boots.

We are so glad that our time in Montgomery overlapped with the time you guys were there. Even with the insane heat, we enjoyed hanging out with you for a couple of hours. It felt like home being with you. See you in Springfield! Safe travels, friends.

Everything we saw in Montgomery was so thought-provoking and powerful…. I obviously had a lot to say about it! My next post will be considerably shorter. 🙂 It was definitely helpful for both of us to be reading the King biography because otherwise we probably would have been completely overwhelmed by the volume of information. Since we were pretty comfortable with the timeline of events, it allowed us to be much more open to the artistic and emotional side of all the museums we visited. The whole experience was extremely eye-opening, and we will definitely put the Memphis Civil Rights Museum on our list for future destinations.

It was fabulous to see you guys and share part of the Montgomery experience with you! Looking forward to crossing paths again soon.

Your post makes me regretful that we came through that area pre-vaccine and none of those places was accessible (even if they were open, which I’m pretty sure they weren’t) to us. Your thorough-as-ever posting is excellent and assuages our regret a bit. I can only imagine how overwhelming it is in both information and emotion.

I’ll bet you were both so happy to have had the A/C fixed and operational, not to mention a lot of the activities being indoors. Here’s hoping the heatwave releases its grip for the remainder of your summer travels!

I have to say that the museums in Montgomery truly exceeded my (high) expectations. I was expecting to be somewhat moved, but I was not expecting to be blown away by world-class art, graphics, and museum design. The city is obviously still struggling with a lot of poverty, but it is really turning its civil rights heritage into a huge differentiating factor. And I am definitely pleased that so many of the activities we planned during this visit were indoors, since the weather was so oppressively hot. We really like to get outdoors, both hiking in nature and walking down city streets, but not when it’s 99 degrees with exceptionally high humidity. Thank goodness for our new A/C!

This is an excellent post and makes me even more regretful that we didn’t get to explore Montgomery when we traveled through the area. Each of these museums seems to bring something different to the table, while adding to the collective experience, and certainly your recent readings about this time period added to your visit.

I’ve seen several blog posts about the lynching memorial and each one has blown me away. That has to be one of the most visually arresting monuments ever designed. It really is too bad the associated museum doesn’t allow photos inside. I think that’s such a short sighted practice and drives me crazy every time. Fortunately, your detailed explanations of what you saw – and, importantly, how you felt to see it – makes up for the lack of photos.

Sorry for the terrible weather. Hopefully things will cool down a bit as you travel north. Speaking of which, I’m looking forward to your posts about Huntsville. I’m thinking there might be some cool rockets????

I was soooooo disappointed that I couldn’t take photos at several of these museums. That being said, a lot of the exhibits included projections, screens, holograms, and other digital media that would probably not show up well on pics. Plus, people taking photos could be distracting for others. And because there is so much original artwork there may be concerns similar to art galleries that prohibit capturing imagery. So I get it, sort of. But I was still bummed. Overall, though, I am so happy that the really good museums in Montgomery incorporate contemporary approaches to engagement, outreach, education, artwork, community involvement, and above all FACTS, instead of just romanticizing the Confederate past. It gives me hope.

We are hoping for better weather, but planning ahead for shady campsites, limited outdoor activities, and doing 100% of our cooking on the grill for the next week or so. Can’t wait to get to Wisconsin.