Any history of Cape Cod is going to have a heavy focus on Pilgrims and whaling, but I discovered a treasure trove of interesting science history when exploring several of the sites within the Cape Cod National Seashore.

Lighthouses as Navigation Aids

One image that is very much associated with New England in general and Cape Cod in particular is that of lighthouses. Not being a boater, I had always assumed that lighthouses served the single purpose of notifying ships of the location of land, to avoid running aground. It turns out that the earliest lights installed on the Cape also communicated important navigation information.

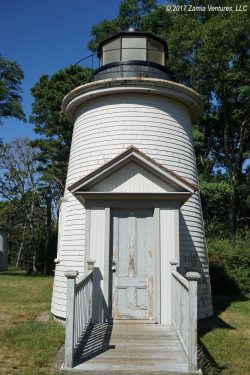

Those early 19th century lights were basically oversized lanterns, powered by whale oil, which made them all look more or less alike. To help mariners locate themselves off the coast of Cape Cod, the lights were installed in unique configurations. Chatham, at the southeastern tip of the Cape, had two twin lighthouses. Nauset Beach Light Station, located approximately halfway up the coast, had a trio of lights known as the Three Sisters. The Highland light, close to the northeastern tip of the Cape, had a flashing signal. These lights were not particularly tall but the placement on top of the high bluff ensured they were visible far out to sea.

As technology — mostly in the form of Fresnel lenses — advanced, the multiple lighthouses were replaced with single lights that featured unique colors and flashing patterns, creating a separate signature for each light.

But the main driver of the changes to the lights was the constantly eroding shoreline of the Cape. As the National Park Service description of the Three Sisters makes clear, the lifespan of a Cape Cod lighthouse is pretty short and often ends with falling into the sea.

The Three Sisters (second iteration) were preserved in part because they were made of wood and designed to be relocated. The Nauset light shown at the top of the post is actually a repurposed version of one of the twin lights in Chatham, which became available when Chatham converted to a single light. I certainly like the thriftiness shown by the effort to recycle the lighthouse versus allowing it to fall into the ocean.

Transatlantic Telegraphs

Meanwhile, Cape Cod also features prominently in the history of transatlantic communications. Unlike Maine, which is obstructed to the east by Canada’s maritime provinces, Cape Cod has a direct path across the Atlantic to Europe, making it the U.S. area that is closest to Europe.

As a result, Cape Cod was the entry point for the second transatlantic telegraph cable to connect the U.S. to mainland Europe, completed in 1879, with a point of origin in Brest, France and traveling via St. Pierre Island, Newfoundland. Prior cables originated in Ireland until activities of French companies put France (and Cape Cod) on the map as a location for international communications. The French Cable House located on Nauset Beach near the lighthouse is the original hut that sat down on the beach to receive the incoming telegraph line as it emerged from the sea and connect that ocean line to inland lines.

The first telegraph cables were laughably slow in transmitting information — a sort of early equivalent of dial-up. The fine folks at Wikipedia inform me that the first transatlantic cable, laid down in 1858, took two minutes to transmit a single character from Ireland to Newfoundland, with the initial 98 word message taking 17 hours to transmit. Despite this, communication between North America and Europe in minutes (or hours) must have seemed like a miraculous advance for people accustomed to communicating via letters carried on steamer ships.

A newer cable was installed in 1897 which ran directly from France to Cape Cod, landing at Orleans, and which remained in operation until the fall of France in 1940. Surprisingly, the modest cable hut — no longer used for the 1897 cable — was not allowed to fall into the sea and today is perched on the Nauset Beach bluff.

Next Up, Wireless Communication

The final part of the Cape Cod communications trifecta involves wireless communications. Guglielmo Marconi, one of those gentlemen inventors of the late 19th century who walked the fine line between “mad” and “scientist”, developed a practical method of transmitting Morse code using radio waves. With communication miraculously untethered from cables, Marconi achieved widespread use of his technology in Europe and the obvious next area of focus was transoceanic communication. Like the cable companies, Marconi initially worked out of Newfoundland, but ended up installing a permanent transmission station in South Wellfleet. From its inception in 1901 the station was the most important U.S. location for wireless communication, to Europe but more importantly to ships at sea.

The long radio waves transmitted by the Marconi method required a huge apparatus — powered by massive electrical current — to transmit and receive messages. Marconi supervised the construction of several different versions of the array, with the final design featuring 200 foot high towers holding a web-like set of heavy metal cables. No doubt the residents of Cape Cod were delighted to be at the forefront of yet another communications revolution.

But the initial excitement soon gave way to some dismay. I can’t improve on the National Park Service description of the issue:

The station’s effectiveness was limited however, so broadcasts were made between 10 pm and 2 am when atmospheric conditions were best. This brought little enthusiasm from local residents, who endured the sounds of the crashing spark from the great three-foot rotor supplied with 30,000 watts. The sound of the spark could be heard four miles downwind from the station. Eventually, the novelty of wireless telegraphy waned.

The Wellfleet Marconi transmission station played an important role in maritime communications, but was closed down in 1917 for World War I-related security reasons. The Marconi technology was soon superseded, locals were not exactly clamoring to reopen the station, portions of the station were removed and recycled, and the entire contraption eventually fell into the sea. Today, all that remains is a simple marker showing the most inland location of the enormous former Marconi wireless station. The Marconi name lives on in the name of Marconi Beach, one of the most popular beach destinations within the National Seashore, which is located just south of the site of the original wireless station. I am glad to know more about the technology that first made this beach famous.

1 thought on “Cape Cod: Home of Communications Innovations”