While our 6-month commitment to daily turtle patrolling is the most significant volunteer activity of our summer, we are also involved in another interesting citizen science project through ANERR (the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve). In our second gig, we are sampling Gulf of Mexico water and beach sand and analyzing it to determine the prevalence of microplastics.

What’s the deal with microplastics?

Microplastics are simply pieces of plastic that are less than 5 mm in diameter. In some cases they are manufactured at that tiny size, such as perfectly round little beads that are used in some cosmetic products for exfoliation / scrubbing. In most cases, however, they are tiny pieces that have broken off larger plastic items. While discarded plastics that are slowly disintegrating are a big source of microplastics in our environment, it’s interesting that quite a bit is not coming from trash. Microplastics are shed by running our polyester clothing through the washing machine and dryer. They are shed by food storage containers when we microwave leftovers. And on and on and on.

What’s truly amazing is that we’ve managed to distribute plastic to virtually every corner of the earth, and especially our waterways. The French marine research vessel Tara, which we visited when it docked in Miami in 2016, has undertaken several expeditions sampling waters around the globe, and recently completed projects focused on the Mediterranean Sea and major European rivers. In this startling report about the Mediterranean expedition, the Tara Foundation notes that the Mediterranean is 100% polluted with plastic. I’ll let them give you the really bad news:

More alarming still, the concentration of microplastics (< 5 mm) in some locations is greater than in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, the so-called seventh continent of plastic, and in numbers of a similar order to plankton, which forms the base of the food chain.

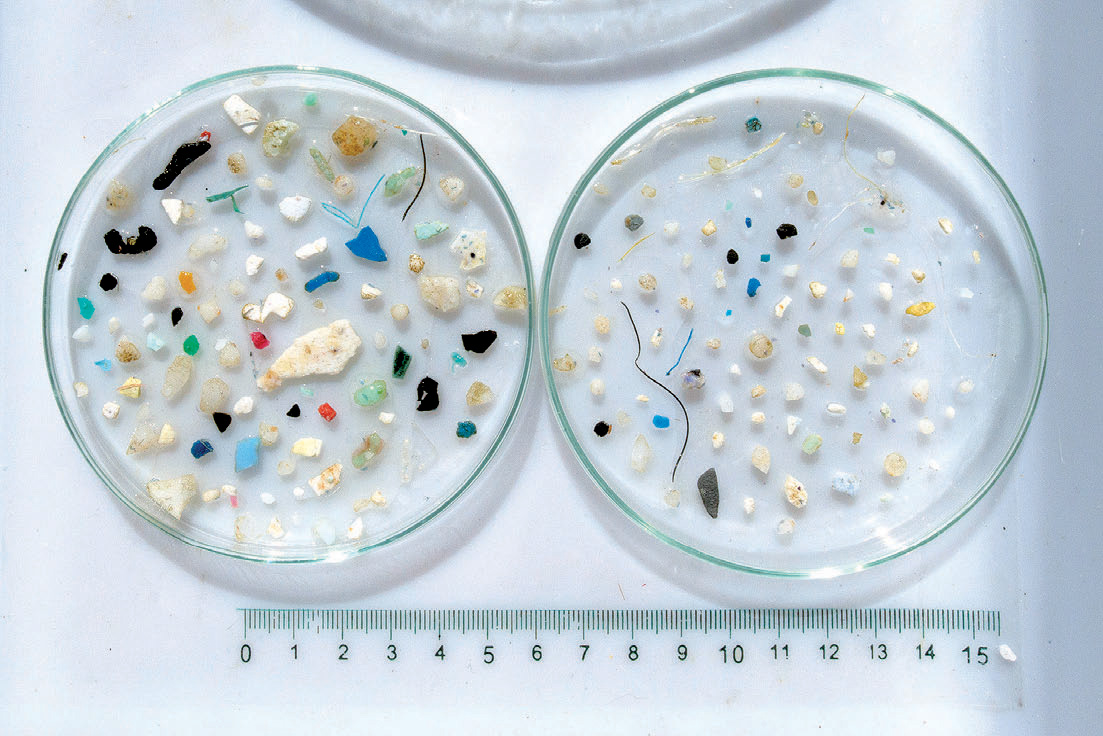

Yikes! By the way, the photo at the top of the post is from that Tara report and © Samuel Bollendorff – Tara Expeditions Foundation.

Research on the health effects of microplastics is still in very early stages, but common sense would suggest that ingesting lots of plastic (and having every organism in the food chain below us ingest lots of plastic) isn’t a great thing. This 2019 statement from the World Health Organization urges more research into the prevalence of microplastics in the environment, particularly in drinking water, and potential health consequences. This May 2021 article in Nature discusses several different research projects looking into possible harmful effects of microplastics on humans and other living things ranging from zooplankton to sea turtles.

Our Project

Our project is part of an initiative developed by Mississippi State University and being implemented all along the Gulf Coast from Texas to Florida to collect and analyze data on microplastics in the waters of the northern Gulf of Mexico. Here in Franklin County, volunteers are sampling at 4-5 different locations on the Gulf and in Apalachicola Bay, and collecting our samples four times per year (January, March, June, and September).

The main contribution of Mississippi State was developing the protocols that all the citizen scientists follow in order to test microplastic levels. The real genius of their process is that, until the very end, it relies on tools made from very simple parts that a person could gather from sources like hardware stores and aquarium supply shops. Seriously, the tool we spend the most time with is this contraption:

So what do we actually do?

Step 1: Get Samples

This is the easiest step and takes less than an hour. We collect our materials on the beach right down the road from our home, and we collect three water samples and three sand samples from an area about 100 yards long. The water is easy to collect in knee-high water, and we just fill liter-size glass jars. For sand, we use a standard metal bucket scoop to collect about one gallon of sand per sample by scooping the top inch of sand along the wrack line in a defined area and smushing it (that’s a technical term) through a sieve into a standard 5-gallon bucket. Then we store each sample of sand in a Ziploc gallon bag. So elaborate!

Allow me to demonstrate:

Step 2: Process Samples

The most time-consuming part of the project is processing the samples to separate the microplastics from the other material, and the garbage-can-based device handles the sand. We fill the garbage can with saltwater for increased buoyancy, and we make our salt water with the amazing and new-to-me product Instant Ocean. The sand goes in the tall tube along with a small aquarium bubbler stone. When we turn on the pump and open the valve at the bottom of the tall tube, salt water begins to flow up the tall tube and agitate the sand. The pieces of microplastics ride to the top on the little bubbles generated by the stone. The outflow of the very top layer of water is captured in a very fine sieve. We run through several steps (run for 7 minutes / turn off air bubbles for a short time / run for 9 minutes / turn off pump for a short time / run again for 10 minutes) designed to agitate the sand and ensure the microplastics float to the top. Finally, we carefully rinse the material on the sieve into glass vials to be examined later. The end result after processing a gallon of sand (several pounds!) is a few small vials of water with suspended microplastics.

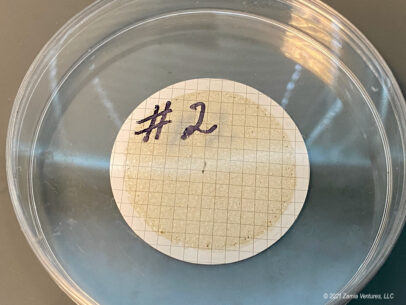

Processing the 1 liter water samples is much easier. We use vacuum-assisted filtration beakers to suck the water through extremely fine filters. The end result is a piece of filter paper to be examined under a microscope. I find the whole thing extremely counterintuitive, since processing the samples means turning gallon bags of sand into little vials of water, while turning our water samples into dry filters.

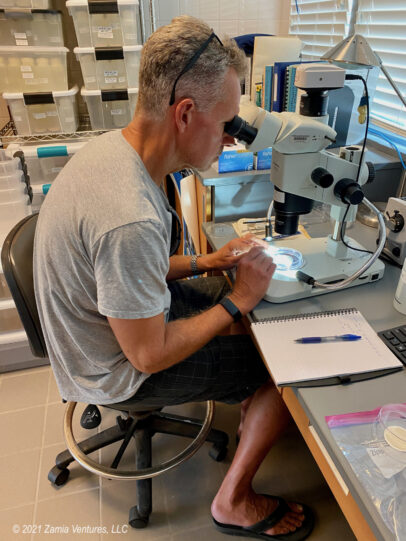

Step 3: Squint and Count

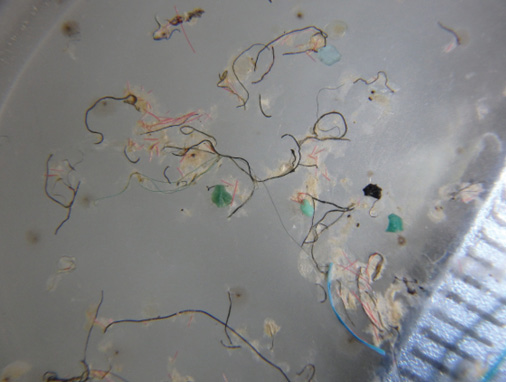

The third and final step is to examine our processed items and count all the microplastics. Lab day is the only day we don’t get wet and sandy, and it’s also the day we get to use the microscopes. I mean, what science project would be complete without some time on the scopes? We carefully examine all our samples and count up and record the different types of microplastics we find: beads (perfectly round), fragments (jagged), films, and filaments. The image at the bottom of the gallery, courtesy of our MSU training guide, shows an example of what we’re seeing in the scopes, with several filaments and fragments visible. The thin metal pointer thingy (that’s another technical term) is an important tool as we examine our samples, since we often need to jab questionable items. If they fall apart on contact, they are organic.

So what are we finding? Sadly, plenty of microplastics. In our first set of water samples, our “cleanest” sample had 30+ pieces of plastic in just 1 liter of water. Our sand samples were even worse, with well over 100 pieces of plastic in our most polluted sample. We overwhelmingly find filaments in our samples, and my speculation is that much of it is being shed by the industrial fishing nets used throughout the Gulf, with a smattering from hobby anglers. The fragments we find could be anything from post-consumer food waste like plastic bottle caps to disintegrated beach toys. While the findings are a bit depressing — and unsurprising — we are glad to have the chance to participate in a project that helps to quantify the volumes of plastic pollution and create a data-driven foundation for improvements in manufacturing, packaging, and waste management.

Wow, that is a lot of work you two have committed yourselves to! The whole process made for a very interesting and informative post. I couldn’t help but be struck by how much plastic is used in the whole process of microplastic detection. It’s like a necessary evil or it will be what helps solve its own problem or something like that! Thanks for being dedicated and caring Citizen Scientists. I hope your posts will inspire others to more awareness and to do the same!

Yes, it is certainly ironic how much plastic is used in microplastic detection! These substances are just so useful that I don’t see them being less common in our lives. I love my synthetic fleece items. The best outcome is probably to create a longer life cycle (eliminate single use plastic items) and improve recovery methods (recycling) to allow plastics to be reused instead of just discarded.

We’re having a lot of fun playing at being scientists. Fortunately this project is a lot less work than turtle patrol — basically two half-days of work at the lab, plus an hour to collect the sample, each quarter of the year. It’s cool to be involved in this without taking on a giant time commitment.

This is fascinating, and also distressing. I’m actually shocked that you’re finding so many micro plastics on St. George. Along the coast of Oregon and Washington, if you look closely, there are a lot of little colorful plastic pieces on those gorgeous beaches. There’s an entire endeavor called “Washed Ashore” in Bandon, OR devoted to creating art (I’m talking BIG sculptures) from the little plastic pieces that wash ashore in Oregon, and I’ve collected many bags of tiny pieces of plastic from the beaches on Lopez Island during our summers there.

But because I don’t SEE the plastic on the beach at St. George Island (other than the random sand shovel or bucket left behind) I thought we had plastic-free beaches. We’ve tried for years personally to reduce our dependence on plastics, but realized that we can’t go completely plastic-free since things like many parts of our RV and our truck are made from plastic, for example. I kind of wish plastics had never been invented. But I guess the only thing to do now, as you said, is to make things last longer and to really up our recycling efforts world-wide. Thanks for the good work you two are doing.

Our home botanical garden hosted a Washed Ashore Exhibit, and it was amazing! But also depressing. Working on this microplastics project had been very eye-opening. Like you, we generally thought of plastic pollution in terms of large, visible items like the junk floating in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The stuff at the microscopic level is still there, just less noticeable. Also, it’s probably harder to clean up than the large items. I doubt much can be done about the micro scale plastics that are already distributed around the world, but hopefully projects like ours can make a difference in future policy and regulation. As you said, it’s virtually impossible to live a modern life without plastics, so we need to figure out ways to either make it more biodegradable or less disposable (easier to recycle).

Yeah, that was depressing – no doubt about it. What is most interesting/demoralizing to me is where these things are coming from. I was under the impression microplastics were mostly the result of plastics breaking down in the ocean. It would never occur to me that they are a byproduct of our laundry, microwaveables, and industrial fishing practices. It certainly makes you question how much of this stuff we’re consuming every year. I just hope the end result of all this hard work you’re doing is actual policy change that makes a difference. I’ve become more and more cynical in my old age about anyone actually ever doing anything about any of these problems. The fact that it’s a battle at all is disheartening.

Anyway, good on you guys – again – for trying to do your part to make the world a bit better.

Oceans are definitely not the only source! It’s just that most stuff ends up in the ocean after originating on land, traveling down a river, etc. The Desert Research Institute in Nevada is doing several microplastics studies, and in one they are analyzing samples of dryer lint collected by volunteers. I didn’t link to that study in the post because they don’t have results yet, but in other projects DRI is finding microplastics in the water of Lake Tahoe, in snow in the Tahoe area, in the bodies of freshwater fish, etc. It is truly a worldwide problem affecting every type of habitat. Just one more handbasket we have made for ourselves.

I do think that policy change is possible – remember when we used to have leaded gas? – but it takes overwhelming evidence of adverse human health effects to move the needle. We’re not there yet with microplastics.