Even after being on the road for almost 8 months, even after extensive reading of reviews, even after plenty of time spent analyzing satellite maps, we are still encountering places that completely defy our expectations. Eastern Oregon is one of those places. We were in the area mostly to see the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, which is notable for its active and ongoing fossil collection work. Unlike the huge collection of dinosaurs at Montana State / Museum of the Rockies, this area’s fossil resources are from the Cenozoic Era, AKA The Age of Mammals, AKA the current era.

Even if we were not attracted by the prospect of fossils of early mammals, Eastern Oregon was a natural stopping point for us as we continued west from Boise, since it gave us a destination that was conveniently located between Boise and Portland. We knew the area was sparsely populated, but we assumed that after spending months in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho we were well-acquainted with the challenges of visiting rural areas. Sure, there would be no large grocery stores, but we were coming in fully stocked from our shopping extravaganza at the Boise Whole Foods.

The three separate units of the monument are spaced fairly far apart, and we camped roughly in the middle of the three units, so our days involved a lot of driving time. We read, but did not internalize, the relatively terrifying travel tips on the NPS website for the monument. In preparing to visit the area, Ken reviewed fuel options, and mused, “I wonder where the people there get gas?” After spending several days driving long distances to the various sections of the monument, we know that the question is moot. There are (virtually) no people. The road in from Boise and the areas around the monument were by far the most desolate and remote places we have visited yet. The main signs of human habitation were herds of cows, but the cows were generally confined to the flatter areas surrounding the John Day River and other waterways in the area. Narrow strips of cultivated fields were surrounded on all sides by steep, seemingly impenetrable mountains that cut off each river valley from its neighbors.

The mountains themselves show off otherworldly colors from the layers of sediments that contain the rich fossil beds. Red, yellow, pink, brown, and even blue-green cliffs line the sides of the valleys we drove through. Where the mountains have developed a layer of soil, the surfaces are covered in sagebrush and other tough plants that can survive in the desert steppe environment that prevails here. It is a remarkable landscape, and it would not have surprised us if the whole area were preserved as public lands. The fact that the roads were lined with mostly private property, and that it was so empty, was just plain weird.

I don’t know which was more unsettling: (a) driving for miles and miles over hours and hours and seeing nothing but a few dozen cows scattered on an otherwise pristine landscape, or (b) driving for miles and miles, seeing just a few dozen cows, and then seeing a mailbox at the end of a dirt drive disappearing into the hills. Of course, there was not a lick of cell service to be found while driving around, enhancing the feeling of isolation. I’m not sure exactly what we expected from Eastern Oregon, but we definitely expected….. something. Not just cows and sagebrush. Despite the lack of other compelling destinations — or perhaps because of that — we visited all three units of the monument, each one stranger than the last, and we have plenty of photos to share.

Sheep Rock Unit

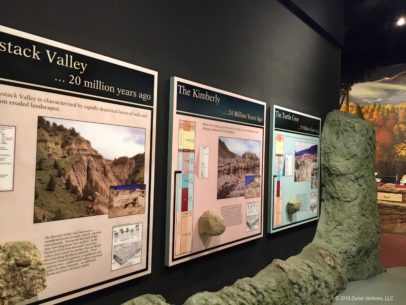

The Sheep Rock Unit is closest to the town of John Day, Oregon (notable for having such modern conveniences as two gas stations and even a few hotels, but still 40+ miles from the national monument) and is home to the park visitor center. The visitor center has excellent interpretive displays showing multiple different time periods from which large groups of fossils have been found at the monument.

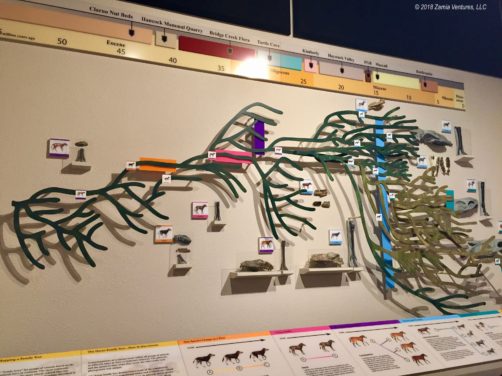

John Day Fossil Beds are notable for preserving complete environments, and not just animals. A very significant portion of the fossils from the sites consists of plant material, including wood, vines, leaves, and seeds, as well as fossilized insects. Each time period that was featured in the visitor center was portrayed in a fully rounded manner, with attention to the predominant climate and the plants and complete animal communities that lived in the area at the time.

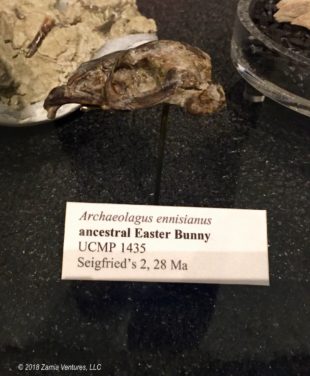

The visitor center displays a large array of original fossils along with helpful descriptions of the forces of sedimentation, fossil formation, and evolutionary changes to various species. Some of John Day’s premier specimens include early ancestors of horses, bears, and big cats. A working fossil laboratory engaged in collection, preparing, and storage is also part of the visitor center, and it was interesting to peer through the windows into these working areas.

Sheep Rock is also home to numerous badlands-style formations of eroding clay, from which fossils are constantly emerging. The Sheep Rock Unit has several areas with intense blue-green (celadon) cliffs which, surprisingly, do not contain copper. The color comes from chemical action on non-cuprous volcanic ash, creating a unique blue-ish mineral.

Hiking through these celadon hills was sort of like stumbling into Oz. Everything was just so blue-green! Even the small streams flowing down the hillsides were a chalky aqua color, thanks to the color of the rocks on the hills.

Clarno Unit

The Clarno Unit is the only section of the national monument where the public can get face to face with fossils in the rocks. The “palisades” rising above the valley floor are rich with fossils, since they were created millions of years ago by muddy lava flows called lahars that swept into valleys and buried everything in their path. The volcanic flows moved so fast that they indiscriminately collected rocks, plants, insects, and animals in a jumble that preserved (in a mushed together fashion) everything in the vicinity. We enjoyed walking around and peering at the exposed rocks in search of fossils, at least for a limited amount of time. It rapidly became apparent that I do not have the patience necessary to be a paleontologist. I can spend all day at a botanical garden, but I was done after about an hour searching for leaves preserved in perpetuity. Still, it was interesting.

Painted Hills Unit

The Painted Hills are considered one of the most photogenic areas of the national monument, attracting photographers from far and wide. As veterans of the Badlands, we were not too amazed to see the different colors on the clay hills, but it was still pretty wild to see the intense colors against the relatively drab backdrop of sagelands.

The conventional wisdom is to visit the Painted Hills during the golden hour (the hour after dawn or before sunset) to see the best colors on these colorful clay hills. While we don’t mind getting up early, we are definitely back at camp well before sunset, so it was fortuitous that we had overcast weather during our visit to the area. Most of my photos of this area look fake, but they are not! The park ranger at the visitor center commented that we would see the colors in the cliffs thanks to experiencing overcast weather, and she was right. While bundling up in rain gear every day was a little annoying, it was definitely easier than getting up before dawn.

Journey Through Time

One of the things that I found persistently amusing is that the State of Oregon has invested in installing really nice signs throughout the region advertising the “Journey Through Time Scenic Byway.” I’m sure the slogan refers to the rich fossil beds in the area, but I spent our whole visit thinking “We are journeying through time — to the 1940s.”

We of course had no modern “amenities” like electricity at our campsite, and our drives featured plenty of reliance on paper maps. To make matter worse, there was the issue of gas station attendants. I believe that Oregon and New Jersey are the only two remaining states that don’t allow mere mortals to pump their own gas. However, Oregon recently enacted legislation authorizing self-pumping of gas (i.e., the “pay at the pump” gas stations that the rest of America has been using for decades) in counties with fewer than 40,000 residents. Since cows are not considered in the population tallies, the areas around John Day Fossil Beds clearly qualify for this benefit. However, none of the facilities selling gas in the area have upgraded to modern gas pumps. Instead, they have single pumps with physical/analog meters that turn over as gas is dispensed. The gas pumps that we saw were literally older than me, and I am not that young! Every gas visit involved driving over a rubber tube to ring the service bell, and hoping that a person actually emerged from the gas station who could operate the ancient technology. I would not have been surprised at all to see James Dean wander out from one of these service stations and straddle a Harley.

In short, our trip to Eastern Oregon involved way more words in this blog post than people. The booming metropolis of Spray, Oregon (pop 160) was closest to our campsite, but needless to say we experienced quiet nights, no competitition for campsites, and an itch to get the heck out of there and back to some semblance of civilization. We’re now happily ensconced in a state park east of Portland. Things we are enjoying about the Columbia River Gorge: traffic on I-84, soothing train noise, consistent cellular connections, full hookups at our campground, and street lights. It’s amazing how a little deprivation will change your perspective.

4 thoughts on “Strange Isolation at John Day Fossil Beds”