For the first 300 years of European exploration and settlement of North America, water was the main mode of transportation. It therefore makes sense that virtually all the historic cities of North America — from Quebec City, Boston, New York and Philadelphia in the north to Charleston, Savannah and New Orleans in the south — initially grew because they served as port cities. As European settlement spread inland, the great rivers of the continent served as highways. In keeping with this emphasis on water travel, one of the official primary goals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition was to find a water route to the Pacific Ocean. The significance of rivers is apparent from a cursory review of a map:

- Place where the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers join to become the Ohio River = Pittsburgh

- Spot where the Cuyahoga River flows into Lake Erie = Cleveland

- The falls of the Ohio River (rapids where travelers often needed to wait for water to rise or fall to make a safe passage) = Louisville

- The confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers = St. Louis

- Place where the Platte River joins the Missouri = Omaha

- Where the Minnesota River flows into the Mississippi = Minneapolis

You get the idea. All of which brings me to the mystery presented by the confluence of the Ohio and the Mississippi. These are obviously two of the great rivers of the continent, yet the place they meet is basically empty. Well, there’s the booming metropolis of Cairo, Illinois (pop 2,831 in 2010). It’s a bit puzzling why there is not a major city in this location.

The area was strategically important in the Civil War, and General Ulysses Grant made it his headquarters beginning in January 1862. The town experienced significant population growth in the middle and later 19th century, but then shrunk to its very small modern size.

The best explanation I can find for the lack of development is the persistent danger of flooding from the Mississippi. Cairo, Illinois is completely surrounded by levees and is in constant danger of being submerged by large floods. During our visit, we couldn’t even get out to Fort Defiance Park — the land directly abutting the confluence of the rivers — because the park was flooded.

Another possible explanation is that the town was just founded too late to experience the heyday of river traffic. By the time the town really started to develop, railroads were already beginning to displace boats as the primary means of transporting goods and people. Some may say Cairo just missed the boat. (Rimshot, please!)

Regardless of the reasons, it’s very clear that Cairo’s best days are long past. The town center features quite a few lovely historic brick structures with very interesting architecture. Unfortunately the buildings still in use, like the churches and courthouse, are surrounded by abandoned structures in various stages of decay. I don’t have photos (I was driving) but there are some good ones in this article. It was a little eerie driving through a quasi-ghost town, but at least I didn’t have to worry about too much traffic while navigating through the area with the Airstream in tow.

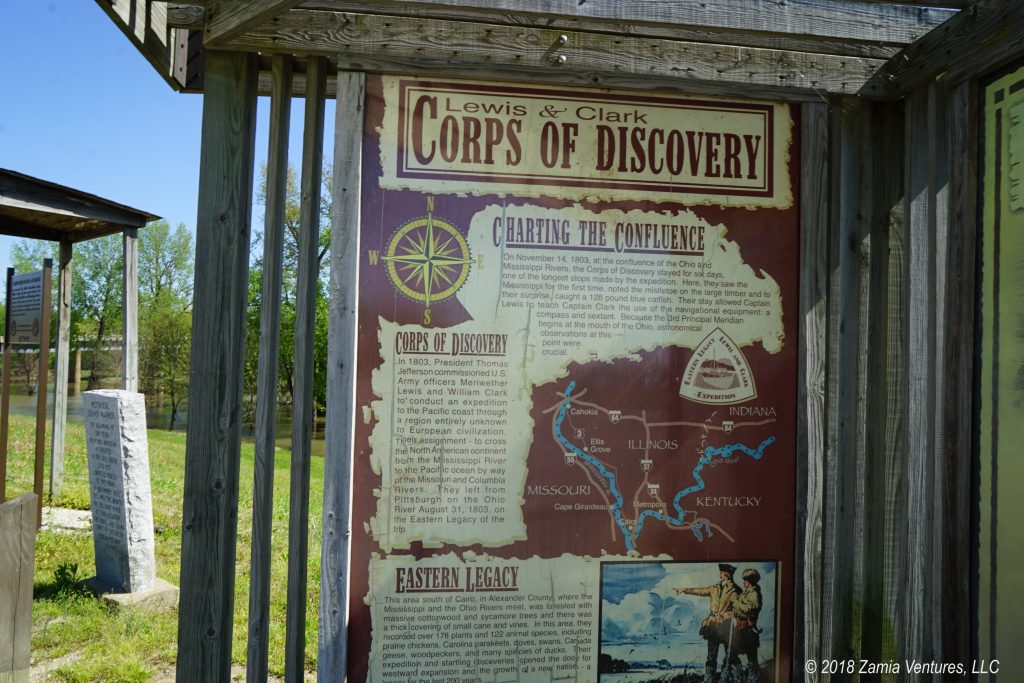

Although there’s nothing here, we wanted to visit the spot where the intrepid members of the L&C expedition first started rowing; coming down the Ohio from Louisville they were going with the current. We of course will be driving our trusty truck instead of walking or rowing upstream, which means it will not take us 2 years to get to the Pacific (we hope). And along the way we’re eating gourmet food and sleeping in climate-controlled comfort. But while the road ahead of us is much less daunting than what the Corps of Discovery faced, it’s still a milestone for us, since we are now officially west of the Mississippi!